This text was originally published in French in issue 11 (1994) of the Cahiers antispécistes journal and was republished in the collective book La Révolution antispéciste (“The antispeciesist revolution”), éd. PUF (2018).

This English translation was prepared by Elisabeth Lyman (proofreading: Holly James) for publication on the Fighting Speciesism website, and revised by the author.

65 min.

Science requires order, which means it needs classifications. This is the first explanation we might naively come up with when we ask ourselves why the notion of species exists in biology. To gain any kind of understanding of its subject, biology is no more able than other sciences to simply consider each of the things it studies one by one – whether individual plants or animals. It has to be able to insert these objects into a structure, thus linking specific facts to a more general group and, conversely, forming predictions based on the individual’s position within this group. Each of the sciences does the same in its respective domain. In geology, for example, rocks can be categorised as metamorphic, crystalline, sedimentary and so on. In astronomy, the stars are classified based on their spectral characteristics, mass and whether or not they belong to a particular sequence (dwarf stars, giant stars, etc.). There are, however, two idiosyncrasies in biology when it comes to classifying objects:

1. Biology has one classification system in particular that has been accorded a more privileged status than any other: a system with a specific (hierarchical) nature that enjoys a special “scientific” reputation.

2. There are political stakes associated with biology in general and with this classification in particular.

More specifically:

1. In biology, there is one reference framework in particular that is seen as representing the absolute truth, the highest level of scientificity. This system is known as the Linnaean taxonomy1 (or, tellingly, simply the “scientific classification”). It separates all living beings into basic categories – now known as species – which, in turn, are sorted into a hierarchy of rank-based categories. Each individual belongs to one category and one category only, and can be placed in other higher categories only via the first. I am a human (my species) and also a mammal (my class) but this second category is not independent from the first; the category of species completely contains the category of class. In other words, it is only because I belong to a given species that I am also part of other categories; I have no other characteristics within the Linnaean hierarchy than those that stem from my species. Conversely, in astronomy, for example, the fact that a star is a dwarf star rather than a giant star does not mean that its spectral type is A rather than F; rather, there are four possibilities: dwarf A, dwarf F, giant A and giant F. The “dwarf star” category crosses the border of the “spectral type A” category. There is no hierarchy among the categories that is designed to completely summarise the position of an individual within the classification system. This is the case for every discipline within the sciences and elsewhere; only biology is governed by a unique, totalitarian classification system.

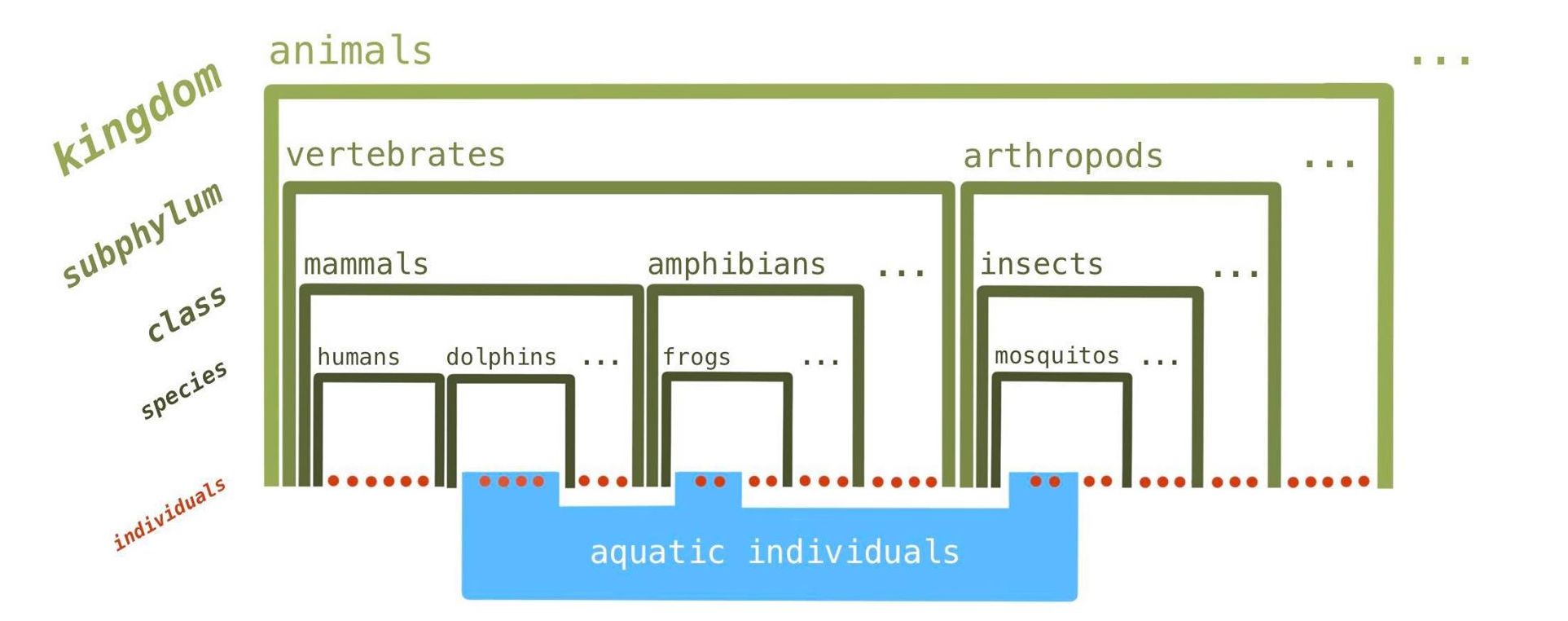

Of course, in each specific field of biology, other classification systems are also used. For example, in ecology, there is a distinction between land and aquatic animals; these categories cross the boundaries of the Linnaean taxonomy, even at the species level – at a certain point there are even individuals, such as frogs, that begin life in the category of aquatic animals (tadpoles) but become land-based animals as adults (see fig. 1). But these other classification systems are always perceived as additional reference frameworks to use on an ad-hoc basis; their status is not considered to have the same level of truth as the Linnaean taxonomy, which is the scientific classification system, the taxonomy2.

2. Through these categories, this “scientific” biological classification creates a specific form of discrimination that is practised by humans against members of other species. Not only is biology a science concerned with living beings, it is also a science that living beings, specifically human beings, are concerned about. It is not neutral, and is even less neutral than other sciences. In the 19th century, it seemed only natural to focus on the Linnaean taxonomy and to create subcategories within each species – in particular the human species. In this way, humanity was declared to be divided into races, and whose boundaries, very conveniently, were found to coincide with those of existing discriminatory political categories (the category of slaves, for example). It was therefore race, rather than species, that summarised all that could be said about a given human from the point of view of the taxonomy. Conversely, modern movements to combat racism have, for the most part, rejected the notion of race altogether, declaring it unscientific. And yet it would appear that the only prerequisite for a category to be deemed scientific is that it be based on identifiable individual characteristics; for example, the category of individuals with dark skin (“black people”) is perfectly scientific3, in the same way the category of right-handed people is. It is not, therefore, the scientificity of classifying humans in itself that was and remains an issue for political debate. The issue is that the Linnaean taxonomy owes its special “scientific” status to something else entirely.

Moreover, the notion of race, and generally any classification below the species level, cannot be consistently integrated into the Linnaean taxonomy, which requires that individuals pass their own taxonomic position on to their offspring. In most cases, reproduction involves two parents, and this rule can only apply if both parents have the same position within the system. But the category of species, as we will see, is defined as the smallest possible unit that enables us to preserve this rule. Sub-species, races and other categories will never be able to gain the same “scientific” prestige that the Linnaean taxonomy enjoys4. In spite of this knowledge, however, many biologists seem to want to extend the Linnaean taxonomy to a level below species, to integrate all genotypical variations into it. Nevertheless, the touchstone of the Linnaean taxonomy, its foundation, remains species. The important thing to note here is that it is on this very foundation – a classification that is not just reputed to be scientific, but is considered to be the only scientific classification system among all the systems that exist – that the widespread discrimination carried out by humans is based.

Anti-racism movements have questioned the scientificity of the notion of human races, focusing instead on the “unity” of our species. This unity, however, is linked to criteria that are evidently more political and ethical in nature than scientific. As I have mentioned, the aim of their critique is not to question the scientificity of the process of classification itself. Rather, they question something specific that has been attributed to the Linnaean hierarchy, something that is in fact ideological in nature. The problem, as I will demonstrate, is that the Linnaean taxonomy owes the special status it has within the domain of the biological sciences to something implicit – an implicit ideology.

We have refused to acknowledge the spread of this ideology among the human species because it would have threatened our unity. Instead, we insist that “all men5 are born equal”. That is to say:

— Equal in factual terms: despite their differences, all humans are considered to have a certain something that is identical, the same essence. This essence is thought to be factual in nature (“all men are born equal” is not presented as a prescription, but as a fact).

— Equal in terms of rights, dignity, etc., which is to say that this supposed factual identity stems from a prescription for equal treatment, an ethical equality. The essence in question, a metaphysical “object”, supposedly has the power to determine what prescription is required.

If the act of subdividing the human species in accordance with the Linnaean taxonomy has the power to threaten the unity of this essence, as well as the notion that we all deserve equal ethical consideration, this means that there is an attribution of an essence hidden underneath the “purely scientific” categories in the system, and in particular, in its core divisions. The Linnaean taxonomy is perceived as the classification system because it is used to classify what is essential. It is this aspect of the system that I would like to examine first of all. As we will see, however, if this role of “distributor of essences” is stripped away, the Linnaean taxonomy is no longer a scientific classification system at all, let alone the classification system. As a result, the object of the system – species – cannot be considered scientific either.

My criticism will explore the following four topics:

I. The notion of species and the entire Linnaean taxonomy, as well as a significant part of the corresponding theoretical framework, were developed before the theory of evolution, in an explicitly essentialist context.

II. Although it has now been officially dissociated from its essentialist theoretical origins, the notion of species remains practically identical in substance to what it was in the pre-Darwinian era. Nevertheless, if it is not supported by the notion of essence, the concept of species can no longer characterise individuals – only the relationships between them. The fact that the Linnaean taxonomy is still regarded as the scientific classification system implies, however, that the concept of species has been implicitly hypostatised6; it is perceived as a reality that characterises individuals and corresponds to the underlying persistence of the essentialist vision.

III. The Linnaean taxonomy is not a scientific classification system at all in the sense that it is not theoretical. The only scientific status it can be said to have is not that of a classification system but, in its “phylogenetic” form, an unconventional, testable (falsifiable) historical hypothesis based on evolution. To consider the taxonomy as such would require us to start taking the theory of evolution seriously and drawing conclusions from it. In fact the opposite is the case: the fact that the taxonomy continues to be linked to essentialism implies a determination to carry on regarding the Linnaean taxonomy as a classification system – as the classification system.

IV. The desire to consider a single, hierarchical classification system as the scientific classification system is in itself totalitarian and as such, indicative of a tendency toward racism. Yet, at the same time, racism contradicts the logic of the Linnaean taxonomy, which ensures that an individual’s position within the system is conserved from one generation to the next so it cannot permit individuals to be classified differently when they are able to interbreed. The Linnaean taxonomy therefore finds refuge in speciesism, perceiving every individual from the same species as identical in essence. But speciesism in turn contradicts this logic if we take evolution into account, which is precisely what biological systematics objects to doing.

I have frequently drawn upon Ernst Mayr’s The Growth of Biological Thought7 for historical data here. Like many modern scientists, Mayr, a highly renowned biologist and systematist who is representative of his field, claims to have taken a position against the essentialist notion of species. We’ll soon see whether or not this is the case8.

I. Essentialism as a historical framework

The foundations of the essentialist theory of species

Though the idea of essence is concealed in the modern notion of species – there is, after all, no place for essences in science – this has not always been the case. We don’t have to go very far back in time to find instances of this notion being explicitly accepted.

The world view that prevailed in the west until the end of the 19th century was creationism. Earth had been created by a god around four thousand years before the Christian era9, along with all living beings, “each according to its kind”10. Once created, these beings reproduced, i.e. they perpetuated their species despite their own ephemeral character.

Species were not determined independently of the visible characteristics of individuals; on the contrary, species were determined by these characteristics. A horse begets a horse, a dog begets a dog, and we can clearly see that horses are different from dogs. It was therefore possible to simply classify species in accordance with this idea: as groups of individuals that resemble one another. But this resemblance, which was transmitted from one generation to the next, was attributed to something intangible and invisible yet powerful, present in each individual, and capable of determining each individual in its entirety, both physically and morally. This something transcended the individual because it was shared with others; it outlived the individual. It was unalterable and had been created along with the rest of the world by God. As for individuals, they were expressions of that thing, which was their essence. They were nothing more than “representatives” of their species (an expression still used today), of the invariable “internal mould”, which George Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788) attributed to the first individual11 created12:

There exists in Nature a general prototype in each species upon which all individuals are moulded (...) The first animal, the first horse, for example, was the exterior model and the internal mould from which all past, present and future horses have been formed.

Within each individual, there was therefore an interior mould, which was either strictly identical to that of another individual or radically different; species were separated by “unbridgeable gulfs”.

Nature’s Plan

There were nevertheless relationships between species. It was evident that not only was there a difference between plants and animals, but also that a cat was more similar to a lion than to a fish. Aristotle had already made the distinction between animals “with blood” and “without blood”, the latter corresponding to the category now known as invertebrates. Nature, according to Aristotle, did not do anything in vain, and given that (according to Christians) it had been created by God, it was important to find out what Nature’s (God’s) plan was at the moment of Creation. The theory was that it should be possible to classify species in divisions and subdivisions. This process did not aim to determine a classification criterion for any particular purpose and separate species accordingly. Rather, it was a quest to uncover a single, pre-existing plan. There was only one “true” variant of biological systematics and the search for criteria was a search for the “true” criteria. The selected groups therefore had to be “true”, or what would be described today as “natural”.

This point of view is therefore the root of biological systematics: the classification system. Each hierarchical division was founded on a specific criterion: the spine distinguished vertebrates from other animals; mammals are animals with mammary glands, etc. The criterion had to be the true criterion, i.e. the criterion determined by Nature’s Plan. As not all criteria could be simultaneously true, a choice had to be made, for example between classifying bats, which have wings and mammary glands, either as birds or as mammals. The history of biological systematics is one of different systems competing to determine the right criteria. Each naturalist had their own version. For example, “Linnaeus, rather misleadingly, called his method the “sexual system”. This terminology reflected Linnaeus’ evaluation of the preeminent importance of reproduction. Reproduction, for him, indicated the secret working plan of the creator”.13

Essentialist theory vs. variations

Individuals were nothing but imperfect representatives of their essence, since it was clear that there were variations within the same species (all horses are not identical), whereas an essence had to be immutable. “Like father, like son” is only true up to a certain point, despite the fact that essence, the thing that was supposed to be responsible for the resemblances between individuals of a given species, was said to be transmitted unchanged. This resulted in a tension between essentialist theory and the facts observed, which can be summarised as follows:

— Species are identical internal moulds that exist within each individual of the same group.

— This internal mould is translated into and can be identified by the external appearance of the individual.

— Nevertheless, individuals of the same species do not all resemble each other completely.

The problem that was beginning to emerge both in theory and in scientific practice, was the following: How can we know if two individuals have the same interior mould or not? We only have direct access to the characteristics we can observe, which are an imperfect translation of these individuals’ essence. Yet the degree of resemblance is difficult to measure objectively and what’s more, the variations observed, even within the same species (between a father and son for example) are sometimes significant. This is why British botanist John Ray proposed in 1686 to eliminate accidental (i.e. non-essential) characteristics for the purposes of determining each species14:

After a long and considerable investigation, no surer criterion for determining species has occurred to me than in propagation from seed. Thus, no matter what variations occur in the individuals of the species, if they spring from the seed of one and the same plant, they are accidental variations and not such as to distinguish a species (...).

The essential characteristics are those that are transmitted. Taken in the literal sense, this criterion gives all hereditary traits a specific character. In the context of the current state of knowledge, which teaches us that individuals are usually genetically unique, this would mean there would be almost as many species as individuals. I will come back to this point.

In the above passage, Buffon speaks of the first individual of each species as a prototype, which is to say the first type. Given that, in his theory, this corresponds to an actual individual, this individual had to have every one of the characteristics for that entire organism. For example, it would have had a certain number of legs, have been a certain colour, and so on. Any individual deviating from this type would be considered atypical. If a particular fly has five legs, when normally a fly has six – if the fly has been maimed, for example, as a result of an accident – this characteristic will be seen as an accidental deviation from its type. This is the typological theory of species, i.e. the variant of essentialist theory in which the essence contains something that can determine the individual in its entirety. It was supposedly possible to find near-perfect individuals in nature that were particularly faithful to their interior moulds. When a naturalist found one such individual, they would take it, conserve it (dead), describe it using the catalogue of characteristics and christen it as the prime example of its species in memory of its primordial type, the original ancestor it did such a good job at resembling. There is only one standard metre in the world, but it is currently possible to find indexes in scientific institutions of millions of “types” of dried plants and animals conserved in formaldehyde (despite never having asked for this honour) which, to this day, are considered the official reference for each species.

Difficult choices for essentialism

The typological notion of species, however, proved difficult to apply in certain cases. In cats, for example, there is no one colour that appears more frequently than any other. Whether a cat is black, white or tabby, it seems arbitrary to say that it diverges from its type. According to typological theory, however, there must have been a first cat, i.e. a type with a very specific colour. This presented an issue for the typological theory of species, but generally speaking, it didn’t challenge essentialist theory. It was enough for essentialists to believe that essence does not have any means of determining an individual as a whole; certain characteristics are free or are at least not entirely determined by essence. In the example of cats, this essence simply contains a range of possible colours (black, white, tabby, but not green, for example). In modern biological systematics, we often get around this by taking several individuals rather than just one and keeping each of them as references to cover the range of possibilities that are left undetermined by species.

These variations, however, remained problematic even for essentialism itself when they were hereditary. I noticed this issue with regard to John Ray’s characterisation of accidental variations in the passage above. If the colour of a cat is accidental, i.e. not determined by its essence, how can we account for the observation that its colour remains hereditary all the same? Different breeds of horses, dogs and so on had been identified. Because the notion of essence was used to explain heredity – the fact that a horse can only give birth to a horse, etc. – the explanation would have been lacking somewhat if it could not determine all hereditary characteristics (if it was not able to explain why, for example, only a white horse can give birth to a white horse). If, on the other hand, we were to specify that essence carried all hereditary characteristics, every single breed would need to be given the status of species. Some 19th-century writers did in fact create a new species for every new variant they found15. The same way of thinking led to an explosion of new human races – black and white, of course, but also Nordic, Hispanic, etc. – each with its own unique essence. But once again, there were two issues that threatened to destroy the very foundations of the theory. First of all, these new species were able to interbreed: Arabian horses had no problem reproducing with European horses. What, then, was the essence of their progeny? They were christened “half-bloods”, which is to say a single individual in which two essences were said to cohabit. This is a delicate metaphysical operation. Much of racism’s efforts has been directed towards compensating for inadequacies within the laws of nature with human laws prohibiting any such “monsters” from coming into being (consider the Nazis’ obsession with racial purity). Next, as a result of this potential for interbreeding, the boundaries that had been determined in nature were often blurred, and the categories observed were often not clear-cut. In other words, according to one classification system, an individual might be classed as b, but according to another, it might be classed as c. Increasing numbers of subdivisions had to be created, but in the end everything became mixed up and the concept of a hereditary, unalterable essence lost all credibility.

In an attempt to keep the institution of essentialism from crumbling, and despite the desire to create subdivisions ad infinitum, which persisted due to the logic of the equation “essence=heredity”, there was nothing for it but to stick to the characterisation of species devised in 1749 by Buffon16:

One must consider as the same species, that which by means of copulation perpetuates itself and conserves the similarities of that species, and as different species, those that through the same means can produce nothing together.

Breeds, therefore, could not be considered species. “Species” could only be used consistently to refer to individuals able to interbreed. Admittedly, in this case, “essence” could not be used to define a complete set of characteristics or even a set of hereditary characteristics – it was no longer able to account for heredity, or at least not in every case – but despite everything, people were still able to believe in the existence of essence and continued to do so until the beginning of the 20th century. It may have been missing a considerable part of its foundations, but the structure of essentialism remained intact. In the 20th century, heredity was explained by factors independent of essence that were more credible (genetic material). The idea of essence, which no longer had the purpose of explaining heredity and had now been contradicted by the theory of evolution, should have disappeared. Should have… but in reality, it continued to subsist. No longer openly, but, as I will explain later on, in an implicit way, hidden within the structure of the Linnaean pyramid.

Essentialist theory at least had internal consistency. The theory alone made it possible to create an authentic classification system. Essences were thought to exist; “cat” existed as an essence, regardless of any relation to the first cat, and would continue to exist conceptually, even if there were no more cats in the world. The theory was based on the existence of essences; the classification system placed individuals into categories that had already been determined. If an individual had the essence of “cat”, it would be classified under the “cat” category. This was a very specific type of classification, however, in that the category of the objects studied was precisely their essence, meaning the category itself covered everything that could possibly be said about the objects, other than accidental deviations, which were not considered to be as important or as “true”. The Linnaean taxonomy, based on essences, thus became not only a scientific classification system, but the scientific classification system.

The touchstone for identifying species in the above-mentioned classification system created by John Ray is reproduction. Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) continued to insist upon this point17:

We imagine that a species is the total descendence of the first couple created by God … What means have we, at this time, to rediscover the path of this genealogy? It is assuredly not in structural resemblance. There remains in reality only reproduction and I maintain that this is the sole certain and even infallible character for the recognition of species.

However, reproduction, which is based on relationships (between two individuals), was not a criterion used to define species. It was, as Cuvier points out, a way to discover, to recognise species, which existed prior to scientific investigation. A species, even if identified through reproductive behaviours, was still said to be an individual characteristic through and through; it was a characteristic that every individual possessed independently of others.

I have dwelt at length on the essentialist concept of species, though one would expect the concept to hold only historical interest, given that the theory of divine Creation has now been replaced with the theory of evolution. In particular, the notion of species should have changed dramatically after the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1858; in fact, given that the idea of species depended entirely on that of essence, we might assume that a shift away from the latter would also have signified a shift away from the former, and that species would have disappeared from biology altogether. We might at least expect species to have been replaced by another concept – one that is not considered superior simply based on a notion thought to directly translate some kind of transcendent entity. Sadly, we will see, this is not the case. Species was and remains the touchstone of biological systematics. The criterion for recognising species is still reproduction. Efforts to subdivide species ad infinitum and to name as many sub-species as possible is as present as ever. Any new species that is discovered also has to be given a type and is christened in turn with its name: the trusty Linnaean binomial nomenclature. The fact that there are variations, the very basis of Darwinism, remains a nightmare for statisticians.

The reality, as we will see, is that the notion of species currently accepted by the vast majority of scientists, the one known as the “biological species concept”, was created simply by gently manipulating the facts – without taking Darwinism into account and without questioning essentialism at all. It is safe to say that the definition of the concept has been modified as little as possible in relation to prior conceptions and that it has remained perfectly compatible with essentialism; in fact, it can be understood as a classification theory only within an essentialist framework, which has merely been superficially rejected.

Not many changes have been made to taxonomical groups superior to that of species, either. Although we no longer refer explicitly to Nature’s Plan today, the groups that are recognised within biological systematics, including new groups, are mostly still named in accordance with one single “true” criterion18. We have, however, been forced to recognise that often, a characteristic – even one that is deemed true – can be lacking in certain ways. For example, while the presence of chlorophyll in plants is what defines the large category of chlorophyllic plants, there are certain plants in this category whose ancestors lost their chlorophyll-processing functions, but which remain in this category nonetheless. They are chlorophyllic plants that do not contain chlorophyll. This loss of chlorophyll is considered to be “secondary”; the plant remains chlorophyllic in spirit.

Faced with these kinds of difficulties, which arise at a critical practical level within several groups in which similarities intersect and which we have no idea how to classify, modern biological systematics turns to what is known as the “numerical taxonomy” method. This method uses computers to process sets of similarities and differences to identify the true classification of individuals once and for all. Dichotomies are no longer based on one single “true” characteristic. Instead, this is replaced by the “objectivity” of numbers (boosted by the presence of a computer), though the aim remains the same. But what could possibly be the point of seeking the classification system if there is no such thing as Nature’s Plan? Some might argue that nowadays, taxonomic groups are related to evolutionary history, and that the aim of taxonomic research is to revisit it. This is where (and I will come back to this point) the phylogenetic point of view comes in19, but it is precisely the point of view that numerical taxonomists explicitly reject. They claim that their “objective” methodology is not based on any hypothesis (a term they see as having pejorative connotations) about the phylogenesis of the species being classified. There is therefore no longer any explanation for this desire to find a single classification system, unless we assume that the notion of Nature’s Plan remains a decisive factor in the thought structures of those seeking to establish the system.

Biological systematics in the form of the Linnaean taxonomy remains the classification system. The debates surrounding the system are still as heated as ever and we continue to agonise over whether certain taxonomic units are “natural” or not. An early 19th century taxonomist would find themselves a little disoriented if they were to attend a biological systematics conference; it’s easier to grasp the basics of modern taxonomy if you believe in divine Creation than Darwin’s theory of evolution.

II. The modern concept of species

According to Ernst Mayr, the modern, so-called “biological” concept of species represents a complete break with the past20:

(a) The old species concept, based on the metaphysical concept of an essence, is so fundamentally different from the biological concept of a reproductively isolated population that a gradual changeover from one into the other was not possible.

And yet in the following paragraph, we find this assertion21:

(b) To a modern biologist, it would seem only a small step from Ray’s modified essentialist definition—“A species is an assemblage of all variants that are potentially the offspring of the same parents”—to a species definition based on the concept of reproductive communities alone. Even closer was Buffon’s definition, “A species is a constant succession of similar individuals that can reproduce together” and whose hybrids are sterile.

Ray was no more a “moderate” essentialist (as Mayr puts it) than Buffon was. He was simply, like everyone else in his time, an essentialist. At that time, there was no notion of species other than the concept of species based on essence. Ray’s characterisation of species cited by Mayr in (b) is perfectly compatible with essentialism, just as Buffon’s is. Mayr speaks of definitions here, but we have already seen in Buffon’s quote above that he believed species were predefined, just like essence (the “interior mould”) and therefore did not require any other definition. Buffon’s statement cited by Mayr in (b) is therefore not a definition; it is simply a recognition technique. It makes sense, then, that there is no explicit talk of essences here. We can see from (b) that the modern concept of species is almost identical in substance to the essentialist concept of species. But in (a), the same author states the exact opposite. What are we supposed to believe?

Mayr refers to the modern concept of species as a “biological concept of a reproductively isolated population” and later states that its definition is “based on the concept of reproductive communities alone”. We will see how the modern characterisation of the concept of species is based directly on how species were identified back then; the theory of evolution has not been brought into play in this theory whatsoever.

Let’s take another look at Buffon’s statement:

We should regard two animals as belonging to the same species if, by means of copulation, they can perpetuate themselves and preserve the likeness of the species; and we should regard them as belonging to different species if they are incapable of producing progeny by the same means.

The specification “and preserve the likeness of the species” does not have the role of a criterion, since this is presumably always the case; it is only there to clarify the idea, and the author has omitted it in the second part of his hypothesis, which, inversely, defines what a species is not. It is therefore possible to paraphrase this statement as follows:

Two species are in fact one species if and only if they are able to interbreed22.

The problem is that this statement appears to draw upon circular reasoning since it requires two species to identify one. It is nevertheless possible to take a group of closely related individuals as a base unit and assume, in principle, that they are from the same species (it is not possible to simply select two separate individuals, given that two males, for example, are not able to reproduce with each other). We are then left with the following:

(i) Individual a is of the same species as individual b if a is a close relative of b, or if a, or a close relative of a, is likely to interbreed with b or a close relative of b.23

For Buffon, as we have seen, this kind of statement did not have the status of a definition; it was a method for identifying existing entities, i.e. species. I will nevertheless demonstrate how certain people attempt to turn this statement into a definition, and how we still end up with a concept of species that is identical to the modern concept, with no reference whatsoever to the theory of evolution.

As a definition, statement (i) does not define the species of an individual from the outset; rather, it defines the binary relationship: “is-of-the-same-species-as”. This should be read as one word – a new word, because it is being defined. I will illustrate this point further presently. The goal, however, is not to understand this relationship as a whole that cannot be broken down; the relationship simply helps us to better understand the concept of species, which is what we are really interested in. How can defining the term “is-of-the-same-species-as” help us to define the word “species”?

There is a method for extracting a concept of category from this kind of expression. The method is based on mathematical relations known as “equivalence relations”, which are reflexive, symmetric and transitive. We can use a made-up placeholder word – for example “droze” – to test whether a relation is an equivalence relation. “Droze” is an equivalence relation if:

— it is reflexive: for any object or individual a, it is possible to say a drozes a;

— it is symmetric: if a drozes b, b also drozes a.

— it is transitive: if a drozes b and b drozes c, a also drozes c.

These three equations need to be true if we want to replace “droze” with “is of the same species as”, read here as several words rather than as a single word . When a relation is one of equivalence, it enables us to divide a set of individuals into equivalence classes. This means the relation becomes synonymous with the phrase “is of the same equivalence class as”. Defining a relation, if it is an equivalence relation, therefore enables us to define equivalence classes at the same time, and to replace the relation between two individuals with a relation between an individual and its class. In a way, to come to the conclusion that we have found a classification, all we have to do is hypostasise the class, to imagine it as a reality independent of the elements from which it is composed.

So is the relation “is-of-the-same-species-as” an equivalence relation? According to the definition in statement (i), the relation is reflexive (an individual is always closely related to itself) and symmetrical (for example, “x can reproduce with y” is the same as “y can reproduce with x”). The transitive constraint, however, poses a problem. There is nothing to suggest that if a (or one of its close relatives) can reproduce with b (or one of its close relatives), and the same applies to b and c, then a and c will also be able to reproduce. In fact, there are examples of the opposite being the case in certain species, which are sometimes called “broken ring species”. Consider the case of black-backed gulls and herring gulls, as described by Richard Dawkins24:

In Britain these are clearly distinct species, quite different in colour. Anybody can tell them apart. But if you follow the population of herring gulls westward round the North Pole to North America, then via Alaska across Siberia and back to Europe again, you will notice a curious fact. The ‘herring gulls’ gradually become less and less like herring gulls and more and more like lesser black-backed gulls until it turns out that our European lesser black-backed gulls actually are the other end of a ring that started out as herring gulls. At every stage around the ring, the birds are sufficiently similar to their neighbours to interbreed with them. Until, that is, the ends of the continuum are reached, in Europe. At this point the herring gull and the lesser black-backed gull never interbreed, although they are linked by a continuous series of interbreeding colleagues all the way round the world.

Can we say that a herring gull “is-of-the-same-species-as” a black-backed gull? We certainly can’t if we refer to statement (i); however, the herring gull “is-of-the-same-species-as” an American gull, which in turn “is-of-the-same-species-as” an Alaskan gull, and so on until we get to the herring gull. Because the relation is not transitive, it cannot be used to define an equivalence class, i.e. the species; we cannot break down the term to say “is of the same species as” without the dashes. If we were to do so, by direct comparison, the herring gull and the black-backed gull would be different species, whereas by indirect comparison they would be the same species. This is where our problem lies.

The only solution seems to be to consider these two types of gull as the same species, along with all of the intermediary types, despite everything. To do this would require modifying the definition given in (i), by performing what is known as a transitive closure:

(ii) An individual is-of-the-same-species-as another individual if the relation defined in (i) can be directly verified, or if it can be indirectly verified through a chain of intermediaries.

This is essentially the same as saying:

(iii) An individual is-of-the-same-species-as another individual if the two are able to have a common descendent in the future.

Although the herring gull does not mate with the black-backed gull, it is still indeed able to mate with the Alaskan gull. Its successive descendents could then eventually make their way around the North Pole and end up with a descendent in common with the black-backed gull.

In this case, it is possible to say we are dealing with an equivalence relation in that it is reflexive, symmetric and transitive, and it is possible, as I have said, to move on from defining the relation to defining equivalence classes themselves. In short, it is possible to extract the notion of species from the relation “is-of-the-same-species-as”. The species of an individual can be defined as the set of individuals that have verifiably been involved in this relation, i.e. those with which the individual is able to have a common descendent. The herring gull’s species in this case consists of all the gulls in the same ring, its “reproductive community”, which exists in “reproductive isolation” from those outside of the circle, the circle having no internal reproductive boundaries. As such, we arrive at the modern notion of species as characterised above by Mayr.

As I have explained, to arrive at the modern definition of species by taking the recognition criterion outlined by Buffon as a starting point, there was no need whatsoever to refer to evolution. Nor did I refer to the notion of essence during this process, but no part of the process contradicts it. Buffon was able to (or rather, had to, if he wanted to take into account the existence of broken ring species) end up with the same notion of species without rejecting essentialism. The only difference was that his research was focused on a characterisation rather than a definition. The transitive closure introduces cases in which two individuals of the same essence do not interbreed, but there is no additional theoretical issue here; “accidental” factors, for example, can also prevent two individuals from reproducing.note]

Given that there have been accidental variations, we cannot be certain whether these could prevent reproduction as well. This in itself poses a problem for essentialism, regardless of the question of transitive closure, because if two groups that are able to interbreed are required to be of the same essence, the inverse is not necessarily the case. There is no way to be sure whether two groups have a different essence; perhaps the factors that prevent cats and dogs from reproducing with each other are accidental, but their essence is the same. In fact, for Linnaeus, essence was not related to species, but to genus, i.e. a group of species. This is illustrated in the “Linnaean binomial nomenclature”, the naming system for species invented by Linnaeus that is still used today. In it, each species is referred to by the name of its genus followed by a qualifying term, for example an adjective. A rat is Rattus norvegicus, which means it is the norvegicus (Norwegian) variety of the Rattus genus. Its essence, what it is, is Rattus; the specific species to which it belongs is seen as accidental. To this day scientists are still attempting to establish the notion of genus as the “objective”, “natural” data, as opposed to higher categories of classification that are recognised as having something of an arbitrary nature. These attempts are, despite everything, also based on individuals’ ability to interbreed (individuals from different species but from the same genus may be able to reproduce, but their offspring will not be fertile).

This does not fundamentally change the link that I have highlighted in this article between the Linnaean taxonomy and essentialism. In terms of speciesism and the value attributed to humans on the basis of their essence, let’s remember that we refer to the “human genus” as well as the “human species”, and that in the current version of the Linnaean taxonomy, there is only one species in the Homo genus: sapiens. It would be just as accurate to speak of “genusism” as of speciesism; in principle, they are the same thing25. Buffon would have ended up with the same species.

It is strange that two theoretical frameworks that are so different – one essentialist and the other officially evolutionary – recognise the same categories. But as we will see, the modern definition of species is implicitly essentialist, precisely because its purpose is to define something about the individual. It is not enough to be able to attribute a category to every object in order to find a scientific classification; it must also be possible to attribute the category in a non-arbitrary way, in accordance with a criterion that relates solely to the individual. So the concept of species, defined as equivalence classes in accordance with the relation outlined in (iii), does not represent a theoretical object; species actually exist in the real world and serve to group together all of the individuals that fall under each respective category. If a new kind of cat is born and the set of individuals able to reproduce with my cat (whose name, incidentally, is Ek) changes, the whole species changes. Ek’s species does not depend only on her own characteristics; it depends on circumstances that have nothing to do with Ek herself. What’s worse is the fact that a being of the same species as b does not only depend on a and b. The introduction of the transitive closure has transformed a relation that was once binary into a relation between three or more individuals. Yet certain people’s desire to consider the Linnaean taxonomy as a scientific classification, the scientific classification, implies that despite this, they believe that Ek is a cat; that is to say they hypostasise the notion of species in order to create the scientific category the individual belongs to. The idea that species are something other than a set of individuals is therefore implicit here. In other words, species exist at a theoretical level. Given that we do not find this idea of species at a theoretical level anywhere in the theory, however26, we are in fact referring to the old idea of essence without explicitly mentioning it.

The only part of essentialist theory that is not present in the modern concept of species is that of type, which was not a compulsory element of the theory anyway. Only if essence contained a complete set of characteristics could it be associated with a type. A type cannot be determined based on an equivalence class defined by the relation outlined in (iii). But despite this fact, types are still omnipresent in contemporary biological systematics. They are also omnipresent in everyday language, as evidenced by the fact, for example, that some people say of certain cats that they are not “real” cats (“my cat isn’t a real cat because he never goes hunting”).

The fact that the “biological concept of species” does not correspond to an actual definition in the minds of modern biologists has resulted in them constantly changing the concept. Mayr, for example, proposed the following in 1942: “Species are groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups”27. Later28, he contemplates the question of asexual reproduction29. The logical consequence of this definition would be, in Mayr’s words, “to call each [individual] a separate species”, which he deems “absurd”. Why would it be absurd? The definition exists and can be applied here: whatever the result is, it can only be absurd if we wish for it to conform to a pre-existing idea of what species is, independent of the definition applied. The idea of each individual having its own species certainly is absurd from an essentialist’s perspective. To get around this issue and make the “definition” of this something that he does not name more applicable, Mayr adds the notion of ecological niches, a solution that “seems to fit most situations better than any other”30. The opposite problem applies to bacteria: their transgressive sexuality would create species containing organisms that are too different from one another. We might expect Mayr to simply conclude that the concept of species is useless in bacteria. We can easily study them without it. But no – the concept of species is a must; it is the truth of any given organism. It is therefore necessary to continue researching until we find the concept of species that “best fits” bacteria, too31.

Biologists clearly find it challenging to eliminate essentialism from their theories – like the rest of the population, incidentally (but that’s another problem entirely). Mayr himself cites this extract from the Origin of Species: “When the views advanced by me in this volume… are generally admitted… [s]ystematists will be able to pursue their labours as at present; but they will not be incessantly haunted by the shadowy doubt whether this or that form be in essence a species. This, I feel sure, and I speak from experience, will be no slight relief.”32 It’s safe to say that this day is yet to come.

III. The scientific status of the Linnaean taxonomy

Creating a classification system involves choosing criteria and classifying objects based on the way in which they fit into the system individually. In terms of the choice of criteria used, it is obviously necessary to take into account the population being studied. If all humans died before the age of forty, it would be hardly worthwhile creating a category for “humans below the age of forty”. But the criteria, once they have been selected, apply to each individual independently from the rest of the population. Whether I am under forty or not applies to me, and would remain either true or false even if I were the only human on earth.

As we have seen, this is not the case in the Linnaean taxonomy. Species are only defined in terms of their relations with the rest of the population. The same applies at higher levels, for genus, family, etc. and is particularly apparent in the methods used in numerical taxonomy, which are arbitrarily based on the “distance” between the characteristics of different species to determine whether or not individuals should be grouped with the same genus, and so on up to the top of the hierarchy. Since we classify objects (individuals, species, genera, etc.) at each level according to their relations rather than their characteristics, it would be correct to say that we are not dealing with a classification system at all, unless we do not consider the question at hand to be one of classifying, but rather of rediscovering the “Creator’s hidden Plan” using this method.

The numerical taxonomy method is not accepted by systematists, who instead use the phylogenetic method (also known as cladistics), created in 1950 by Willi Hennig. The cladistics system is based entirely on evolution rather than on actual characteristics of individuals. The system therefore regards the Linnaean taxonomy as a simple reflection of genealogy or a historical record and not as a classification system at all. Mammals, for example, is a valid (monophyletic) group within this hierarchy, if and only if the group includes every descendent of the last common ancestor33. Instead of the Linnaean hierarchy, this system provides a set of scientific hypotheses relating to a very specific object – evolutionary history – which are verifiable, i.e. falsifiable, in principle. This hierarchy cannot be determined by agreement. We can only make hypotheses and attempt to test them. In particular, in cases in which we do not have access to the necessary palaeontological data, it is not possible to determine a “classification”. This is a situation that commonly occurs throughout the scientific field but is not considered a particular cause for concern. Yet for most biologists, it is unacceptable. They need their classification; they need the biological systematics classification. It is no doubt this pressure that has led several proponents of cladistics to abandon what was once the very foundation of their theory as a method for translating evolution and return to a method which, like the numerical taxonomy method, aims to uncover “Nature’s Plan” by comparing characteristics. Once again, evolution was proven to be incompatible with the foundations of the Linnaean taxonomy.

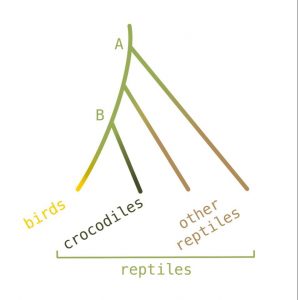

Once of the major criticisms of the phylogenetic method was that it grouped together things that people did not want to put together. The genealogy of birds and reptiles in figure 2 illustrates this. It is in fact thought that all birds descend from a specific reptile B, which is also the ancestor of crocodiles. The last common ancestor for the group containing birds, crocodiles and other reptiles is A. It also contains all the descendents of A. The group is therefore monophyletic. But if the group that only includes reptiles – crocodiles as well as other types – also has the same common ancestor as A, the group needs to include birds to be considered a monophyletic group as they are also descendents of A. Traditional biological systematics, however, has established the group containing reptiles based on their similarity. Birds, on the other hand, have evolved a lot since their divergence from ancestor B. We are loath to put them in a group with reptiles because this does not seem to correspond to “Nature’s Plan”. We want to be able to say that crocodiles are reptiles, that they have ontological similarities with other reptiles that birds do not have. We want the Linnaean taxonomy to reflect this truth. We therefore criticise the phylogenetic method because it lacks this degree of divergence between groups. If, however, we accept this method for what it is, we require the theory to do no more than reflect evolutionary history. The method does not deny the fact that birds have changed significantly since their divergence from crocodiles. It simply isn’t particularly concerned with the matter.

To ensure that the Linnaean hierarchy continues to reflect the truth about living beings without completely ignoring evolution, the vast majority of the scientific community today has adopted what is called the “evolutionary method”. The method retains the spirit of the Linnaean taxonomy but integrates evolution as if it were simply another characteristic that should be taken into account. Mayr, who supports the method, also calls it the “eclectic” method because it draws upon all available resources. The method does not have any clear theoretical status, a fact that reflects the hidden presence of an underlying theoretical object – “Nature’s Plan” again – and anything that can help uncover this object is valid.

The Linnaean taxonomy truly struggles to digest Darwin. In fact, modern creationism, which is still alive and well in certain countries, is more than happy to take advantage of these contradictions. Creationists are able to simply take the Linnaean taxonomy word for word. Each individual has its own species; either it is a human or it is a monkey. Species are perpetuated via reproduction; a monkey cannot give birth to a human. The typical response of a modern biologist is to say that biological systematics should not be taken literally. But how should it be taken, then? What exactly are species?

IV. The Linnaean taxonomy, racism and speciesism

The desire to regard one single, hierarchical classification system as the scientific classification system is totalitarian in itself. Taken literally, this means that from a scientific point of view (that is, in reality) we are one thing only: our species. The basic category I have been slotted into summarises everything that can be said about me from a scientific point of view. To know my species is to know my genus, family, order, class and phylum.

Because humans are very diverse and their differences, far from appearing accidental, are transmitted from one generation to the next, the Linnaean taxonomy finds it difficult to stop at species. If it is to summarise all that is essential, and if all humans are different, it has to subdivide the human species. It has to make a distinction between races and attribute an essence to each one. A black person is a human, then a mammal, but first and foremost they are black. Just as this logic does not accept any groups containing only certain cats and certain dogs – such a group “does not exist” and would not be a “scientific category” or a “natural group” – it cannot accept the attribution of a real, existing status to a group that contains only certain black people and certain white people. A group for labourers, for example, does not exist; a black labourer is black first and foremost, and has more in common with a black CEO than with a white labourer.

The Linnaean taxonomy cannot, however, distinguish between different races of humans. This is firstly because all humans are able to interbreed, and it is difficult to maintain the idea of hereditary transmission of essence when two different essences together make one single offspring. Secondly, racism against humans has been prohibited since the end of the Second World War.

The Linnaean taxonomy therefore retreats and takes refuge in the boundaries of species, where this kind of discrimination is permitted. We are humans, they are sheep, for example, so we have the right to eat them. They do not have the same essence as us. An unbridgeable gulf exists between them and us. We humans are, on the contrary, all identical; identical in essence, at least in terms of the essences that are recognised by science. Our differences are not biological34.

We are humans, chimpanzees are chimpanzees. We are not members of the same species and we do not reproduce with them. Our revered parents were also humans, while theirs were chimpanzees. From one relative to the next, our ancestors have all been humans. That is, until we go back, say, some 300,000 generations – around six million years ago. Here, we find an individual who holds the peculiar position of being not only our most venerable of ancestors, but also the ancestor of chimpanzees35. Chimpanzees can also stake their claim over this individual.

Of course, all of these people are dead. But let us imagine that some of them come back to life, a handful distributed along two genealogical branches that divide from this venerable common ancestor and result in humans on the one hand and chimpanzees on the other. According to Jared Diamond36, humans began to settle in the Americas around 11,000 years ago. No reproductive issues have been found to exist between these peoples and Europeans. The same is undoubtedly true for other populations37. It is therefore reasonable to assume, by extrapolating from this data, that if we brought as few as 600 ancestors in total back to life (fewer would probably suffice)38 on both sides of the two genealogical branches, we would be required to place humans on one of the two extremities of a “broken ring” species, similar to that of the gulls outlined above. Chimpanzees would be at the other extremity.

So are chimpanzees and humans part of the same species or not? We are different species, biological systematics tells us. But not for any reason relating to humans, nor for any reason relating to chimpanzees. They are not even considered different because of any factor that can be deduced from comparing the two. Humans and chimpanzees are different species because the intermediaries between happen to be dead.

But how can biological systematics be the only classification system we refer to if its classification methods are based on such arbitrary criteria, such incidental criteria, which have nothing to do with the individuals being categorised? What’s worse, the system claims to be the only scientific system. Why? The only possible response to this question is that the non-existence of these intermediaries is not regarded as accidental. If it is a coincidence, it’s a “happy coincidence”; the hand of Providence separates us from chimpanzees, allowing humans – and only humans – to be a different species from them, the only ones created in the image of God, according to his great Plan39.

To a certain extent, the factor that the Linnaean taxonomy considers as accidental is the existence of evolution. The result itself is essential. It corresponds to “Nature’s Plan” and claims to reflect it. According to the Linnaean taxonomy, the human species is different in essence from the species of chimpanzees and evolution is nothing more than a story: the story of how the Plan was implemented.

Anti-racists tell us that race is not a scientific concept. This observation is correct, despite the “evidence”. But they have not always been able to give good reasons as to why. They say that racism is not scientific because all humans are able to interbreed40. This is true in the context of the Linnaean taxonomy. But by using concepts from the Linnaean taxonomy to refute racist claims, anti-racists are supporting a system that, by its very logic, is susceptible to revive racism over and over again.

Racism is not a scientific concept first and foremost because it has its roots in the Linnaean taxonomy, which, as an intrinsically essentialist theory, cannot claim to be scientific41. The Linnaean taxonomy constantly threatens to revive racism42. But perhaps one needs to be anti-speciesist to see this.

The Linnaean taxonomy needs to be scrapped once and for all. Biologists might say that this is something of a harsh conclusion. So let’s just start by no longer referring to it as the classification system. What is it, then, when stripped of this status? Nothing. If it is not the classification system, it falls apart and the scattered pieces it has relied on to justify its classifications return to their independent existences. Morphology, ecology and natural history all exist, and they can be developed and combined without the hegemony of one single classification system. We can classify individuals as large and small, as trees or grasses, as aquatic or land-based as necessary. We can even classify individuals based on whether or not they descend from the last common ancestor of ducks and turtles if we so desire.

As for species, we may well conserve the concept of speciation to denote the phenomenon specific to the biological world whereby, as a result of reproduction and sexuality, populations are formed, within which genetic material can be exchanged and which are reproductively isolated from other groups. But this would not be a classification of individuals. It would be a phylogenetic concept involving a large number of individuals. In fact, speciation is generally accompanied by divergence at some level or other between groups. When an individual belongs to a certain reproductively isolated population, this fact more often than not correlates with other characteristics the individual possesses. The size an adult can grow to is generally smaller for cats than for lynxes, for example. But this correlation does not in any way imply a return to species as a criterion for objective classification. If we are studying size, then size is the classification criterion, not species. In the same way, in the domain of ethics, if we are talking about whether or not an individual is rational, then any classifications we make will be based on this criterion rather than species, even though humans are generally (but not always) more rational than other animals. And from my point of view, according to the criterion of sentience, we would put human embryos in the same category as plants.

Incidentally, the degree of correlation between species and individual characteristics can vary wildly. Clinical microbiologists generally need to know more than just the species of a germ, which will often not tell them whether the germ is pathogenic or resistant to antibiotics. Conversely, in mice, for example, there are “twin species”, which can only be distinguished using extensive biochemical analyses. The issue here is that the basic criterion for two individuals to be classified as part of the same species – ability to interbreed – corresponds biologically to a medley of heterogenous phenomena. The fact that two individuals are not able to interbreed may stem from a lack of sexual attraction, a morphological or behavioural incompatibility that prevents the individuals from mating, an incompatibility between the mother and the foetus, a genetic, metabolic or hormonal problem, or any other issue – without even taking into account (both current and future) geographical barriers or changes in the direction of the wind (which sometimes plays a role in pollination). Indirect interbreeding also depends, as we have seen, on the existence of individuals from a third group. Species, which claims to be able to account for everything, does not in actual fact represent anything definite. The concept of species only possesses the fundamental value we attribute to it because it is the key to the ideological system that accompanies it.

In terms of everyday language, we can continue to call a cat a cat, but we can also call a frog a frog, a worm a worm and a tree a tree. These last three categories are not recognised species or even recognised groups of species in the Linnaean taxonomy. If we call a cat a cat, we can also call a black person black. As for Ek, regardless of whether she is a cat or not, I will continue to call her Ek. I will also continue to hope that a day will come when individuals are simply what they are, with their history, stories, desires and lives – without being “first and foremost” anything else at all.

1. I will simply refer to the system as “Linnaean” hereinafter, although it has of course evolved since the time of Carl Linnaeus.

2. “Taxonomy” is a synonym for classification system. But in biology, when scientists speak of the taxonomy, they refer exclusively to the Linnaean taxonomy.

3. In dermatology, this category is in fact very relevant. Of course, it is a vague category – there are many gradations between light and dark skin. But a rock can also be metamorphic to a greater or lesser extent and this does not invalidate any other geological classification that can be attributed to it based on this characteristic.

4. It is neither the sometimes imprecise nature of these categories, nor the fact that they vary depending on the point of view adopted, that render them unscientific. No branch of science requires all categories to be completely accurate and totalitarian. The problem is that we cannot integrate these sub-species into the Linnaean taxonomy.

5. That is to say humans.

6. Hypostatise: treat or represent (something abstract) as a concrete reality. Oxford Dictionary online.

7. Ernst Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982.

8. The inspiration to dig deeper into the impact that Darwinism should have had (but did not have) on our thought systems came from James Rachels, Created from Animals: The Moral Implications of Darwinism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

9. In the 18th century, geologists began to think that the earth was much older. In 1779, Buffon estimated the figure at 168,000 years (Mayr, p. 316). But the dogma of a divine Creation continued to subsist, almost intact, until Darwin’s publication of the Origin of Species in 1858, and remained rife among biologists until the beginning of the 20th century.

10. Genesis 1:24 for example.

11. This could be either a male or female individual.

12. George Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, L’Histoire naturelle, 1749, cited in Mayr, p. 261.

13. Mayr, p. 178

14. John Ray, The History of Plants, London: Clark, 1686, cited in Mayr, p. 257.

15. Mayr, p. 263.

16. Buffon, L’Histoire naturelle, cited in Mayr, p. 262.

17. Georges Cuvier in a letter to C.M. Pfaff, cited in Mayr, p. 257.

18. This is less the case in botany than in zoology. While botanists may speak of “angiosperm” or “compositae” as the “defining” characteristic of a group, there are also “caesalpiniaceae” for example, named after a botanist called Césalpin.

19. The phylogenesis of a group is its evolutionary history.

20. Mayr, p. 271.

21. Ibid., p. 272.

22. This means having fertile offspring, a condition implicit in the idea of “perpetuation”. I will assume this to be the case in the passage that follows.

23. The concept of “close relative” could be made more precise, or left ambiguous – it doesn’t matter either way here. Note that the expression “is likely to” can be interpreted in many different ways (but this, too, is another topic entirely).

24. Richard Dawkins, “Gaps in the Mind”, in Paola Cavalieri and Peter Singer (eds.) The Great Ape Project, New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1993.

25. Since there were accidental variations, we could not be sure that these too could never prevent reproduction. This was indeed a difficulty for essentialism, but independently of the question of transitive closure, since although two inter-fertile groups must always be of the same essence, the reciprocal was not necessarily true. We could never be sure that two groups were of different essence; perhaps the reasons that prevented cats and dogs from reproducing with each other were merely accidental, their essence being the same. And in fact, for Linnaeus, essence referred not to the species but to the genus, i.e. to a group of species. This is reflected in the "Linnaean binomial", the system of naming species that he invented and that still forms the basis of nomenclature today. Each species is designated by the name of its genus followed by a qualifier, such as an adjective. The Rat is Rattus norvegicus, i.e. a variety of Rattus, a Rattus of the norvegicus (Norwegian) variety. Its essence, what it is, is Rattus; the particular species to which it belongs is seen as accidental. It is also worth noting that attempts are still being made to establish the notion of genus as an 'objective', 'natural' datum, in contrast to the higher taxonomic categories that are recognised as possessing a certain arbitrariness; and that these attempts are, despite everything, also based on inter-fertility (individuals of different species but of the same genus would produce viable, but non-fertile, offspring).

This in no way changes the link I establish in this article between Linnaean systematics and essentialism. As far as speciesism and the essence value attached to the fact of being human are concerned, it should be noted that we say "human genus" as well as "human species", and in the current Linnaean classification the genus Homo has only one species, sapiens. We could just as easily talk about genrism as speciesism, it would essentially be the same thing.

26. We could make the category of “cat” scientific by identifying all the genetic characteristics that an individual is required to possess to be able to reproduce with at least one of the cats currently in existence. As such, we could define cats using individual rather than relational characteristics. On the one hand, it should be noted that this kind of reification of the concept of cat has never been attempted; this is because the task would be far from possible at our current level of scientific advancement, and above all, because we consider the concept of “cat” to have already been implicitly reified (the essence of “cat”). On the other hand, species would no longer be separate in theory: if there is no actual animal that can reproduce with both actual cats and lynxes, there is nothing to say that such an animal could not exist. Safeguarding the principle of the separation of species might suggest that there is only one species of living things in the entire world!

27. Definition cited on p. 273.

28. Ibid., p. 283.

29. “Sexuality” in this sense does not refer to the existence of two sexes, but more generally the exchange or recombination of genetic material between different individuals. Hermaphroditic living beings, and those which, like certain bacteria, exchange genes independently of reproduction, can be said to have a sexuality in this sense. There are, however, also living beings without sexuality: certain plants for example practice exclusive self-fertilisation.

30. Mayr, p. 283.

31. Ibid., p. 284.

32. Darwin, The Origin of Species, cited in Mayr, p. 269.

33. Absurd definitions of the concept of monophyly frequently come up in the literature; Mayr, for example, (p. 232) says that a taxon is monophyletic “when all members of a taxon [are] descendents of the nearest common ancestor”. If this is the case, then any group of individuals is monophyletic! I believe that the omission of the fact that the group must also include all the descendents of this ancestor is due to Mayr’s preference for the so-called “evolutionist” system, which I will address later.

34. In this case, what are they? Surely biology, the study of life, also covers humans, which are living beings too? Differences between humans are not seen as accidental either but are perceived to participate in yet another order, the “strictly human” order (or the order of free will).

35. One of the reasons for resistance to Darwinism was undoubtedly that it reversed the traditional hierarchical sequence that requires that we venerate our parents, that they in turn venerate their own and so on. The respect we owe our ancestors grows each time we go back a generation, so how is it possible that at some point in time we end up with an ape?

36. Jared Diamond, The Rise and Fall of the Third Chimpanzee, London: Random House, 1991, pp. 100-101 (renamed The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal in the third edition, released in 2006).

37. For example, humans that lived in Tasmania before European colonisation had been isolated for 10,000 years (Diamond, ibid.).

38. Using the same type of extrapolation, we can estimate that at least three would be required in total (one on each branch plus the common ancestor). In fact, there are two groups of chimpanzees that do not interbreed, and whose last common ancestor lived some 2.5 million years ago (deduced from Richard Dawkins’ article, cited above). On the other hand, the Neanderthals, who diverged from our ancestors (the “Cro-Magnon” people) over 130,000 years ago and died out 40,000 years ago, are classified as the same species as us. We do not really know, however, if they could cross-breed with Cro-Magnons (Diamond doesn’t think so but others do). Taking this example as a borderline case, through extrapolation we reach a figure of 70 ancestors to revive.

39. The idea of potentially considering humans and chimpanzees as the same species within a broken circle came from Richard Dawkins’ article cited above. Dawkins, more than others, seems to have managed to shake off the tight grip of the essentialist conception of species. As a sociobiologist, however, he is propagating in its place an ideology that I feel is also essentialist: that of genes. I’m not certain that we are better off with this system in all cases.

40. With reference not to racism, but sexism, certain ancient philosophers raised the ranks of both sexes to separate species. According to Giulia Sissa, in “Philosophies du genre” in G. Duby (ed.) Histoire des femmes en Occident, vol. 1, p. 73: “In the language of modern science, we are prohibited from saying that the terms male or female correspond to species, because the species is defined by the capacity to reproduce with individuals that conform to the individual”. The verb “prohibit” that Sissa uses here is a little strong and seems to imply that we should understand this idea not only in a scientific sense, but also in a social sense – precisely because a species, far from being a mere scientific object, has its own unique essence.

41. The Linnaean taxonomy was a scientific theory – albeit a false one – at the time when it explained its theoretical foundations, i.e. divine Creation, essences and Nature’s Plan.

42. Perhaps, on an unconscious level, this is why we sometimes call racism “the foul beast”. The non-human, a victim of speciesist discrimination, is seen to support the argument, to be a symbol of discrimination between living beings based on their essence. But the animal does not stay in its place: discrimination makes a counterattack on humanity in the form of racism. The beast has become foul, rather than staying in its slaughterhouse.