This is the English translation of "Le subjectif est objectif", initially published in issue #23 (2003) of the journal Les Cahiers antispécistes.

177 min.

Abstract: The emergence of animalism, and hence of serious consideration for the sentience of non-human animals, makes the traditional division of the world between nature and humanity untenable. Sentience, which was viewed as the prerogative of the human species, is in fact part of the physical world, and science must account for it. The aim of this article is to set out some of the constraints that a sentientist physics must meet.

This issue, known as the “hard problem of consciousness” (David Chalmers, 1995), has been the subject of numerous attempts at resolution or dismissal. The common flaw of these attempts is that they approach sentience as if it were a purely descriptive question, without reference to ethics.

Yet not only does the objective existence of sentience (a.k.a. subjectivity) bring ethics into play in an essential way, but so does the existence of the “material world” itself. For the sake of consistency and completeness, ethics should be defined as the theory of the prescriptive in general, that is, of the right answer to the question "What to do?"*; in particular, ethics includes prudence (concern for one's own future interests). Far from being a human specificity, ethics is a fact of all sentient, deliberative beings, since they must answer this question; non-human animals are, like humans and in the same basic sense, moral agents.

It is often said that prescriptions, unlike descriptions, have no truth value (that they are neither true nor false). However, an examination of the general foundations of our knowledge reveals that, in the absence of rigorous foundations, we have only an impossibility of not believing in the existence of the material world; and that this same impossibility holds concerning the existence of prescriptive truths. If the reality of the prescriptive is ill-founded, it is no more so than is our belief in the very existence of the world. What's more, these two impossibilities mutually support each other.

The vision of the world that current physics gives us makes its evolution equivalent to the execution of an algorithm. The reality of the execution of an algorithm, however, is only conventional and is therefore incapable of producing sentience (qualia). Adopting the distinction made by Roger Penrose between computable determinism (determinism that can be solved by an algorithm) and determinism in general (potentially non-computable), and on the basis of the impossibility of not believing in the reality of the truth value of prescriptive propositions, I conclude, like Penrose, that the physical world cannot be governed by a computable determinism. Sentience appears as a physical phenomenon, that may be deterministic but not computable, governed by laws that we do not yet know.

I conclude by outlining criteria for recognising the presence of sentience in a given organism.

Sentience, the central object of all ethics and of all action, is a reality of the world. It is a reality in itself; an objective reality, one that does not exist merely from some private point of view. In the same sense as a table or a stone are made of matter, our brains too are made of matter; thus, sentience is a potential property of matter in general. Its existence is a fact of physics, and it is the task of physics to give us an account of how sentience is linked to other aspects of reality and to show us how to determine when, where and with which qualities (suffering, pleasure and other qualia1) it occurs.

Despite this, present-day physics is incapable of making room for sentience in its description of the world. The problem would not be solved by discovering some new phenomenon or some new law. We need a complete overhaul of our ideas of reality and of physics. I do not have the keys to such an overhaul; I will be content here with showing why I believe it necessary, and suggest a few conditions that it will have to satisfy.

My reflections are in large part inspired by the views of the English mathematician Roger Penrose as expressed in two of his works2 in which he argues that our current physics is unable to explain mental processes. He considers specifically our capacity to understand mathematical reasoning, a capacity he says cannot be simulated by the execution of an algorithm; this limitation follows, he argues, from the well-known Gödel incompleteness theorem (1931). I believe that this reasoning is very important, but not quite conclusive. Between the lines in the works of Penrose, I see the basis of my own central argument: the inescapability of the internal, subjective point of view, and the fact that this point of view makes it impossible to build a theory of the world without attributing to the subjective, that is, to sentience, and also to the truth-value of prescriptive assertions and to the reality of freedom of choice, the status of facts. It's on this basis, I believe, that can be confirmed Penrose's conclusions, particularly his assertion that the evolution of the world cannot be entirely subject to a computable determinism. If the world is deterministic, it must be so at least partly in a non-computable way, that is, in a way that is not algorithmically reproducible.

Penrose reasons on the basis of one of the most abstract, and specifically human, forms of thinking, specifically mathematical reasoning. What his works suggest, however, is that all authentic forms of understanding – including very practical reasoning, of the kind certainly many non-human animals are capable of – necessarily comprise a non-algorithmic process. Authentic understanding implies the perception of the truth of certain facts, whether these be the approach of a predator or some mathematical truth; it cannot be reduced to the necessarily insentient execution of an algorithm. I will argue that sentience, intelligence (the faculty of understanding), freedom and ethics (the non-algorithmic search for the right answer to the question “What to do?”*) are closely connected and that consequently intelligence, freedom and ethics are properties of every sentient being.

This will give us the means to discern, or rather to better found, a number of criteria that we feel natural to resort to when we wish to determine if a given being is or isn't sentient; such as the non “automatic” nature of its behaviour or the presence of tissue of a certain kind, such as nervous tissue. It will give us indications concerning the place of sentience in evolution. It will allow us to found, as true, our moral obligations towards all sentient beings. Lastly, it will imply the necessity of reconstructing our conceptions of physical reality and will allow us to sketch some constraints that these new conceptions will have to satisfy.

1. Conflicting Certainties

My assertion that our current physics is unable to account for sentience may come as a surprise to some. Indeed, it is at odds with that of quite a few philosophers, including several antispeciesist philosophers. Peter Singer, for example, spends eight pages in Animal Liberation3 countering the Cartesian position according to which animals are insentient and feel nothing at all. Singer puts forward several arguments, all of a scientific nature, without ever mentioning a problem with the scientific status of sentience itself. His arguments concern the behaviour of animals, the presence of nervous tissue and the evolutionary relevance of pain. On the same basis, he argues against sentience in plants4. Another frequent argument is the presence in some animals of certain chemical substances, such as endorphins mentioned by Joan Dunayer in her article “Fish: Sensitivity Beyond the Captor's Grasp”5. Following my experience, antispeciesist activists quite generally tend to believe that the scientific status of pain and sentience is unproblematic and that our inability, for example, to determine whether or not an ant can suffer is only the result of a lack of attention on the part of scientists to the issue.

This attitude sharply contrasts with a view very frequently shared precisely by persons with a scientific background and who claim to speak for a certain rationalism. Their tendency is instead to declare the question of whether a given animal is sentient as meaningless. Erwin Schrödinger, one of the founders of quantum mechanics, expressed this idea – that he didn't share – very clearly, in the answer he imagines a “rationalist” would give to the question “What kind of material process is directly linked to consciousness?”6:

A rationalist may be inclined to deal curtly with this question, roughly as follows. From our own experience, and as regards the higher animals from analogy, consciousness is linked up with certain kinds of events in organized, living matter, namely, with certain nervous functions. How far back or “down” in the animal kingdom there is still some sort of consciousness, and what it may be like in its early stages, are gratuitous speculations, questions that cannot be answered and which ought to be left to idle dreamers. It is still more gratuitous to indulge in thoughts about whether perhaps other events as well, events in inorganic matter, let alone all material events, are in some way or other associated with consciousness. All this is pure fantasy, as irrefutable as it is unprovable, and thus of no value for knowledge.

Mind and Matter, ch. 1

This position, which claims to be “rationalist”7 discards as meaningless the issue of animal sentience (consciousness). It does accept, however, without qualifications, that “we” are sentient – “we” being human beings. It treats our own sentience as an empirical fact, one that is part of the reality of the world, that is furthermore linked in some way to “nervous functions”, in other words to ordinary observable physical events. But outside the human species – and a few “higher” animals – the status of sentience changes radically. For “lower” animals and inanimate objects, the claim is not that they lack sentience; rather, it is that in their case the issue of sentience is meaningless. It is no longer, in their case, in the realm of facts.

These two sides have in common that they see the issue of the scientific status of animal sentience as unproblematic: the pro-animal philosophers because they believe that it has essentially been solved; the “rationalists” because they regard it instead as meaningless. I wish to call into question these two placid certainties; and in particular, that of “my side”, of those who struggle for the respect of the interests of animals. Indeed, the opposing position, which dominates among scientists, has its reasons; and to dialogue with these scientists and with our society as a whole which trusts these scientists, and to answer their arguments with sincere and convincing counter-arguments, we must recognize these reasons. More broadly, reality belongs to us as much as to anyone; we must not allow that in the name of science, that is, in the name of reality, the existence or relevance of animal sentience be denied. We must thus understand the real difficulties there are in making room for sentience within the scientific point of view, and start looking for ways to solve them.

This question has direct practical consequences for the interests of non-human animals. Florence Burgat has described8 the tendency among researchers of the INRA (French national institute for agricultural research) in charge of the issue of animal well-being to view the object of their study as a non-issue, as a mere reflection of “social pressure”, of a fantasy of the ill-informed public opinion (ill-informed because out of lack of scientific vision laypeople take seriously the idea that animals may have authentic well-being). Their studies will consequently aim at contenting this social pressure as cheaply as possible. The well-being of animals will be measured by their health, a criterion seen instead as “objective” and itself measured in terms such as growth rates and other criteria very much in harmony with the interests of the tradesmen, these interests being for their part viewed as very real. When scientists have the mission of studying what is, and believe that animal suffering is not, or – equivalently, as they see it, that the question of animal suffering is meaningless – any serious social consideration of animal interests is impossible.

2. Humans and Stones

The central thesis of this article is twofold, both supporting and opposing each of these two certainties. It posits:

— the inescapability of the subjective point of view, and the impossibility of not believing that ethical assertions – also called prescriptions – possess a truth-value and that sentience and free will are objectively real;

— the impossibility of integrating sentience and the above other facts into the framework of physical reality that still dominates our minds today.

These two impossibilities lead to a contradiction if one takes this conception of physical reality for granted. I will return to each at length, but I also believe that there is a hazy but widespread and persistent awareness of this clash in our culture. The two assertions are rarely articulated, and the contradiction to which they lead is rarely brought to light. Instead, we divide the world mentally into two radically dissimilar compartments: we treat it as made of humans on one side and of stones on the other. The two contradictory assertions are each viewed as true, but separately: one as true in the world of humans, the other in that of stones.

Let us take up the “rationalist” position depicted above by Schrödinger. It starts by accepting sentience as a fact in the world of humans: “According to our own experience, (...) consciousness is connected...”. Consciousness, therefore, is a reality in human beings. Since these are part of the physical world, one could imagine that the same concept of sentience would be applicable everywhere in this world; not that sentience is necessarily present everywhere, but that where it is not present, it is at least absent. But this is not what this “rationalist” position goes on to say; it tells us that beyond the limits of the human world9 the very question of sentience is a matter of “gratuitous speculation”; to such questions “no answers can be given”. Outside the human world, sentience is a concept without meaning.

Schrödinger's “rationalist” does not, however, completely deny that the laws governing the non-human world also apply to the human world; sentience, he says, is connected to certain kinds of events within matter. But he does not specify in any detail this “connection”; and if there is a connection, it is not clear why its presence or absence should not remain discernible outside the human species, including anywhere “down” the ladder of animal species. So he does not seem to be really convinced of the possibility of establishing the said connection. Others, who are less attached to their reputation as “rationalists”, will explicitly make “man” a domain ruled by different laws than those that govern mere matter; they insist that we are both body and spirit. This was the position of Descartes, who is often regarded as one of the main founders of rationalist thinking. Today, such attitudes are often less openly proclaimed, and what is displayed is a kind of schizophrenia elevated to the status of an article of faith; on the one hand, one claims to accept the laws of modern physics in their entirety, and on the other, one maintains that the human being is of another order. This is typically the religious-secular attitude; it is the one promoted by the Catholic Church, and which it still blames Galileo for not having displayed, or not enough.

The general rule is to admit in principle that the human being, including the nervous system, must surely be subject to the same laws of physics as the rest of the universe; but this statement remains vacuous, devoid of any operative power. The complexity of the nervous system serves as both a good reason and an alibi; a good reason because this complexity is real and would make it impossible to analyse in detail, particle by particle, all the events that take place in a brain; an alibi, however, because, beyond the petition of principle, one feels, confusedly or clearly, that complexity does not really make any difference, and that sentience simply cannot arise from this kind of physics which, basically, describes the world as a set of billiard balls evolving “mechanically” – that is, according to laws of computable determinism.

This division of the world between humans and stones extends to virtually all our concepts. At the heart of our legal system is the distinction between persons and things; everything that is not human is a thing, including all non-human animals. At the heart of our philosophy is the opposition between culture and nature; only humans have to do with culture and everything else belongs to nature. Our universities are systematically divided into literary disciplines on the one hand, which study the mind and the “humanities”, and the scientific disciplines on the other hand, also known as hard science (as hard as stones), which study rocks, trees and mice. Sociology and anthropology belong to the former, ethology and chemistry to the latter. A gulf exists, it is said, between humans and other animals; the former think and decide freely while the latter are driven by instinct as a stone is by gravity.

Animals: grains of sand among the stones

The radical Cartesian exclusion of all non-human animals from the realm of sentience is intimately linked to the division of the world into humans and stones, and this in turn is linked to the double impossibility mentioned above. The animal question is thus directly involved in the solving of this double impossibility.

If the world were really made up of two easily identifiable categories of objects, a sharp conceptual partition could be defensible. We could consider that some concepts apply to one category of objects but not to the other. This would be the case, in particular, for those that underpin our ethics, in their various forms. Even without a precise definition of the notions of sentience, autonomy, dignity, free will and so on, we could see that all the signs that spontaneously lead us to believe that a given human possesses one of these characteristics are satisfied by all humans and by no stones. Therefore, given any object of the world, we would need no other criterion than that of its belonging or not to the category of humans to allow us to decide whether it should be viewed as a moral patient, that is whether we should consider it for its own sake in our deliberations.

This is the world as humanism would have it, as our culture in general would have. Yet this is not how the real world is, as we know very well. Already within the human species, not everyone displays, at least clearly, the signs that I have mentioned; there are embryos and fetuses, the comatose and the profoundly mentally impaired. It is above all the moral status of embryos and fetuses that has been debated, because of the issue's practical importance and also because of the obvious continuity in the development from the fertilized egg to the newborn and beyond. If there is a chasm between things and people, it is quietly and effortlessly that the embryo seems to cross it, at some moment we are not even able to determine.

However, this gap is awkwardly contained by invoking the fact that the beings in question, even if they do not possess the features of a typical adult human, are at least destined to acquire them (in the case of embryos), or used to possess them (in the case of the comatose); or possess them by essence, though by “accident” they do not (in the case of the profoundly mentally impaired). The partition of the world into persons and things is thus saved.

It is the non-human animals who make this view untenable. Apart from human beings, there are not just stones. The world is not made up of two categories of objects that are sufficiently distinct for the problem of ethical criteria not to arise. It is not obvious that a chimpanzee is not sentient and has neither dignity nor free will. And if there is doubt concerning chimpanzees, there is doubt too in the case of cats; and in that of fish, that of octopuses, ants and jellyfish, and perhaps even plants. The coral is an animal, related to a jellyfish, but does a coral not look like a stone? Is there any doubt concerning the stones themselves? Probably not, but we would like to know why.

The animal question, by simply pointing at the existence of animals and thus to a prima facie continuity between the world of humans and that of stones, forces us to acknowledge the need for a criterion of moral patience that can be applied to any object in the world. All objects of physics are thus, at least potentially, objects of ethics; the question of their possession of this or that ethically relevant feature – and first among these, of sentience – can, for each of them, be answered positively or negatively, but is never without meaning.

Therefore, the solution that our society adopts to “solve” the double impossibility, which is to seal off the two conflicting theses from each other, each considered valid in its own domain, breaks down. These theses instead meet and collide in a common domain, that of the non-human. We cannot believe that “asking how far down the ladder of animal species there is still some form of consciousness” is a question without meaning; we will need to answer it to determine whether or not we have moral obligations to these non-human objects. This will be true even if we adopt the ethics most hostile to the consideration of non-human animals; if our criterion is not sentience but the possession of rationality, for example, we will need to be able to apply it to any object in the world, even if our intention is to show that, in fact, only humans are rational.

There then remains no point in trying to preserve the domain of the human from the indignities of physics; we must accept that there is only one world and that we are fully part of it; and that sentience, or any other characteristic that we deem relevant to ethics, is of that world, and as such belongs to physics. We must recognize that ethics and physics have the same field of study, the same world. Ethics cares about the humblest pebble, at least in the sense that its criteria must be able to tell us whether and why we should care about it or not.

The criteria of ethics must apply to all objects of the physical world, and it is only by physical means that we can determine whether or not these objects satisfy these criteria. If our criterion is sentience, we can only determine whether an object is sentient by observing it. And we know that everything we observe – the movements, sounds and so on it may make – are physical occurrences, and are related, through the laws of physics, to processes taking place in the object. If we believe that these observed occurrences are indications of the object's sentience, while they are caused by physical processes taking place in the object, sentience itself must be a physical phenomenon. The same reasoning applies to any other ethical criterion one might wish to adopt.

The ongoing crisis of physics

It follows that we have no way out of the double impossibility without altering our conceptions of physics. In the following sections, after examining in more detail the first impossibility, namely the inescapability of the subjective point of view and the impossibility of not believing certain things, I will turn to the reasons for the second impossibility, that of incorporating sentience and other subjective features into the dominant view of physics. One might answer: very well, but modern physics is all but unassailable, and cannot be subverted just because of the ethical problem of the moral status of animals. I recognise the strength of modern physics. However, I also know that it is in deep crisis and that it has lost its foundations. The solidity that is generally attributed to it is largely due to its practical accomplishments, to the impressive power that it gives us to master matter; but also to its alleged capacity to provide a consistent and intelligible view of the world. However, it has lost this capacity since the advent of quantum mechanics in the 1920s. The previous picture, now obsolete, of the way physics described reality has nevertheless remained dominant by default, as a picture of ideal physics, both in the minds of the general public and in those of a vast majority of scientists, even those who are familiar with quantum mechanics. It has remained so precisely because quantum mechanics has given us no credible alternative vision.

I believe, however, that this classical ideal of a computable, billiard-ball determinism is itself inconsistent and ultimately indefensible; this is because it is incompatible with sentience, but also because, if its logic is carried to its conclusion, it self-dissolves into a purely mathematical construct devoid of substance. Therefore, we should not hope to solve the crisis of modern, quantum physics by returning to the previous paradigm, as physicists such as Einstein dreamed of doing in the early days of quantum mechanics. Rather, we must draw on the “quirks” of quantum mechanics, and on the constraints that follow from the reality of sentience, to try to imagine what an alternative worldview might be.

I will explicit later (section 5) the elements of the structure of this pre-quantum physics that serve my argument. I will not attempt to paint a picture of quantum mechanics, however, and will only refer where useful to some of its features. There are good introductory books on quantum mechanics on the market that give an idea of the strange structure of this theory, the most orthodox interpretation of which denies the existence of an objective reality10.

The cry of the carrot

If taking the animal question and the issue of sentience seriously has profound implications for our physical conceptions, I believe that conversely a reflection on physics, and at least an awareness of the inadequacy and inconsistency of our traditional conceptions of physical reality, can allow us to move beyond empty debates and start providing valid responses to some of the objections that we, as animal activists, receive. One example of such an objection is the infamous “cry of the carrot”. Beyond the obvious bad faith behind it, this objection expresses almost explicitly the unease that derives from the impossibility of integrating sentience into our vision of the physical world. We do not get the answer “What about the cry of the carrot?” if we argue in favour of oppressed Chechens; these are humans, and so the question of what physical criterion justifies ethical consideration for them is not asked. But if we care for non-humans, even for some as close to us as pigs or cows, we implicitly show that we do not believe in the partition between humans and stones; our criteria must then necessarily be physical. We are thus referred to a physical phenomenon – the squeaking sound of a carrot being grated – and are asked how we can distinguish it from a cry, from a real expression of suffering, since we do not limit this notion of suffering to the human world alone, but view it as part of the physical world, the one that includes pigs, carrots and stones.

We can already answer, of course, that carrots have no nervous systems and so on. But we have to admit that we don't know why these criteria are not arbitrary. What is it about nerve tissue that makes it the unique site of potential suffering? What we lack is a theory of suffering, and a global vision of the physical world that makes this theory possible. From then on, we will be able to tell from the outside whether or not this or that phenomenon that we observe – a certain sound, for example – corresponds to suffering, without needing to be “in the shoes” of the carrot any more than we need to be in the shoes of an electron to determine its state.

3. The Argument by the Impossibility of Nonbelief**

One may distinguish three kinds of “reasons to believe” the truth of an assertion:

A. Demonstrative reasons (facts and reasoning that make the assertion probable, such as believing that tomorrow it will rain because the weatherperson says so and is rarely wrong).

B. Ethical reasons (in particular, for the utilitarian, it is right to believe something if doing so will increase the total happiness in the world).

C. Causal reasons (any cause of which the belief is an effect; such as the fact that most people believe in a certain religious creed because their parents and relatives believed in it).

It may seem odd to view a purpose as a reason for believing something (reasons of type B). However, for acts in general, a purpose is usually viewed as a valid reason.

One may think that the ideal reasoning in favour of a thesis must be of type A, the model of which is perhaps mathematical reasoning. In such cases, one does not appeal to the advantages for the reader of believing in the truth of an assertion (which would make it an ethical argumentation, type B) and one does not try for example to hypnotise the reader into believing in this truth (an “argument” of type C). Whether the reader likes or not that in a right triangle the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides, that is what he or she is shown.

Only type A reasons for belief can be a valid answer to a question of type “Why do you believe...?” An answer of type B, that is, “I believe it because it is better for me (or for others)”, cannot replace a reason of type A11. Nor can I answer that I believe the assertion because of my upbringing, or because my neurons are configured in such and such a way (answer of type C). Such answers may well actually be true but are not answers to the question as asked.

My wish is to show that ethical (i.e. prescriptive) assertions have an objective truth-value, and thereby to show in particular the objective reality of sentience and of free will. I would be happy if I could base these developments solely on type A reasons. But I cannot.

Shall I then turn to a type B argument, and simply make you desire to believe what I enjoy believing? Or find a way to persuade you by rhetorical tricks that my ideas are correct (give you a type C “reason to believe”)? That is not my intention. I believe that I am justified in using yet another form of “argument” in this case. It does not consist in giving a reason to believe, but in highlighting the fact that we already actually do believe, and can but believe12. Henceforth, acknowledging this fact is only a matter of consistency.

One may find such an argument weak since it is not a demonstration. My response is partly ad hominem, but not, I think, without force. It consists in noting that it is this same form of argument that ultimately underpins everything we believe, starting with our conviction that there exists a world.

This last fact is actually universally recognised; I will get back to this in a moment. What is remarkable is that while being recognised it is generally ignored, the impossibility of basing our belief in a real world on pure reasoning being perceived as a sort of philosophical curiosity that detracts nothing from the good standing of this conviction; whereas the corresponding impossibility in the ethical domain – the impossibility of basing the truth of ethical propositions on pure reasoning – passes for irrefutable proof of the relative or conventional character of these, or, in the views of religious people, of the need to base them on faith in a god.

On the contrary, I think that the truth of ethical (prescriptive) assertions is as well-founded as that of those assertions classically called “descriptive” such as those that describe material realities13. Both are based on the same impossibility of nonbelieving certain assertions despite the impossibility of proving them. If my argument is to be considered weak, it cannot be more so than our belief in the existence of the world; which should be enough for almost any purpose.

Before we discard this argument as too weak, we should grasp its full meaning. The impossibility of not believing that grounds it is not a mere difficulty; it does not refer, for example, to the psychological suffering that nonbelief would cause. It refers instead to an impossibility that is inherent to our way of being in the world. Let us consider that, because of our very presence in the world, because of our situation as sentient beings, it may be impossible for us not to believe something. It is then futile to pretend not to believe it. Any theory we build that contradicts this belief would be impossible to take as true without believing both one thing and its opposite; that is, it would be impossible to take seriously as true, once we become aware of its implications for our inescapable belief. This does not, of course, preclude us from speculating, imagining false what we cannot believe to be false; we may perhaps draw interesting conclusions from such speculations, but cannot believe the world thus contrived to be real.

I now come to the substance of my argument; my first step will be to highlight the impossibility of our nonbelief in the reality of the truth-value of ethical (that is, prescriptive) assertions.

4. Ethics

The impossibility of universal nonbelief

We often know clearly whether or not we believe something. I believe that this is now Saturday, and I know that I believe it. But sometimes it is not so easy. A good example is the question of faith in Christianity, which is central to that religion since the necessary and sufficient condition for being “saved” is to believe in Jesus (in his existence, his divinity, his resurrection, etc.). Hence the nagging concern for every Christian: “Do I really believe?” The simple statement – the “profession of faith” – is not enough. The story of Jesus walking on water and of Peter sinking because his belief that he could do the same was not strong enough shows well that we do not always know whether we believe something or not, or to what extent we believe it; for Peter rises, believing that he believes, but not believing enough; he sinks, and Jesus, somewhat perversely, asks him: “O thou of little faith, wherefore didst thou doubt?”14.

In this story, sinking or not sinking represents a supernatural test of belief. A more mundane test is this: if we believe something, it will be reflected in our decisions.

Do we believe in the existence of a physical world? I don't mean whether we believe in the complete validity of some specific physical theory; I mean, in a minimal sense. For example, do I believe in the existence of the keyboard in front of me? The answer must be yes; the fact that I am typing on the keys to write this text is explained by my belief that this action will change something in the world. I may not know very well what the world is, what matter is, and what it means for it to be changed. But I do know one thing: that it will change something for sentient beings. If I type on the keys, tomorrow I will be able to read what I will have written; and perhaps others will read it too. I believe in the existence of the world at least as a basis for a causal chain such that depending on how I act, sentient beings – myself, at least – will be affected.

The fact that I type on this keyboard thus testifies to my belief in the existence of the world, at least in this minimal sense of “existing”.

This, one may say, is trivial. But it means that we are many to believe in the existence of the world! All sentient beings do so, as I see it; but for the moment we will accept that this belief seems plausible at least for all typical adult human beings – for the non-comatose, for example. They eat and hence believe in the existence of what they see on their plates, or at least in the fact that in some way the movements they perform will cause or remove some sensation of pleasure or of hunger.

An unimpressive result, perhaps, but one that contradicts a tradition that goes back at least as far as the Greek sceptic Pyrrho (4th-3rd century BC), who claimed to doubt the very existence of this world. According to Diogenes Laërtius, Pyrrho believed so little in the testimony of his senses that he only avoided falling off cliffs thanks to the actions of his friends***. This is a rare case; yet, if this account may testify to Pyrrho's nonbelief in the existence of those cliffs (leaving aside doubts about what he would have done in the absence of his friends), it does not imply his nonbelief in the world in general. Quite the opposite: for why then did he put one foot ahead of the other, if not to move forward, or at least to relieve the urge to move – which by itself implies a belief in some effect, never quite immediate, of his actions?

In fact, Descartes, taking up this same question of the ultimate foundation of our beliefs in the existence of the world, began by “doubting” everything; but this doubt was only provisional, heuristic, and did not imply practical consequences15:

(...) so that I might not remain irresolute in my actions, while my reason compelled me to suspend my judgement, and that I might not be prevented from living thenceforward in the greatest possible felicity, I formed a provisory code of morals, composed of three or four maxims (...).

These “three or four maxims” are practical and imbued with solid common sense. They aim, as Descartes says, at felicity (happiness), that is, at a sensation. Descartes derives action from belief (“judgement”) since he fears that in the absence of any belief he will remain “irresolute in [his] actions, while [his] reason compelled [him] to suspend [his] judgement”; yet he claims to be able to compensate for this lack of belief by a “provisory” (provisional) morality. It seems clear, however, that this morality itself necessarily presupposes a belief. The first maxim, for example, “was to obey the laws and customs of my country”; he, therefore, believed in the existence of that country. Descartes thus never really ceased to believe in the reality of the world; he was never irresolute in his judgements on this point. His doubt, which was provisional, was only about their foundations.

By these examples, I want to suggest that the existence of scepticism, philosophical or otherwise, concerning the existence of the world does not imply the existence of any real doubt on this subject. This is not to say that these people are faking it. Descartes himself did not really claim to have doubted the existence of the world. Others may have sincerely believed they had such a doubt, but that doesn't imply that they really had it16.

But my point is not simply to note that particular persons did not really doubt everything, or even to assert that no one ever really entertained such a doubt; it is to show that such a doubt is impossible, because of our situation – because of the situation of every deliberative being, and therefore, I believe, of every sentient being.

Our situation is that we must, at every moment, decide. It is not that it is in our interest to decide; it is that it is impossible for us not to decide.

Let us imagine that we do not believe anything. Then we do not believe that our action will have any particular effect. Why then should we bother to act? We could just as well do nothing. But why do nothing? To avoid getting tired? If we do not believe anything, we do not believe that acting will tire us, nor that doing nothing will tire us less.

Nor can we decide without reasons. When we are irresolute, we look for a reason to decide one way or the other; only with such a reason can we decide. Yet, as long as we remain irresolute, we have at least decided one thing – namely, to decide nothing else. We could run around, or take some other decision; if we don't, it is because we have a reason not to, if only, for example, not to tire ourselves unnecessarily. Descartes, in order not to “remain irresolute”, adopts a moral system, that is a system of reasons for deciding one way or the other; but he does not choose just any moral system. When he states his “three or four maxims” he also justifies them. He does so based on practical, “reasonable” reasons, which he believes in, despite the “doubt” imposed on him by reason.

Descartes, therefore, believes in reasons for deciding, in the “factual” sense; that is, he believes in the existence of a certain country, namely, the one in which he lives, in the existence of its laws and customs and so on. But he also believes in these reasons in the prescriptive sense: he believes that these are reasons to decide to act in a certain way. He believes in the existence of prescriptive reasons.

In short:

— it is at every moment impossible for us not to take decisions;

— we cannot take decisions without believing in reasons for doing so (prescriptive reasons);

— it is therefore impossible for us not to believe in reasons for taking decisions (prescriptive reasons).

Inside and outside viewpoints

It is worth emphasising here the position from which this conclusion is reached. This is what I call the “inside viewpoint”. One could imagine describing the same events – a person deliberating, then deciding and acting – from an outer point of view, as a physical system going through a sequence of states according to certain laws. Perhaps we will then identify some of these states as certain beliefs; and find that the system always happens to be in a state of belief in one thing or another, and that this state determines the system's subsequent evolution, and in particular determines its future actions. No doubt will we also try to explain this state of belief by the laws of motion of atoms, or, at another level, by Darwinian mechanisms of evolution. This outside point of view is valid in its principle, since we are part of the world, and are therefore physical systems; such descriptions and explanations are necessarily possible. Nonetheless, however legitimate it may be, this outside viewpoint cannot abolish the inside viewpoint. The outside viewpoint observes and explains our belief; but the observation and explanation of our belief are not our belief, and do not, by their mere existence, abolish our belief.

However, it may happen that how we observe and explain one of our beliefs constitutes a reason to cease believing it; for example, when we explain an optical illusion. We may then abandon the belief. But it may also be that this is not the case and that we do not abandon the belief, perhaps because we have not been convinced by the explanation, or because it does not really seem to contradict the belief, or for any other reason; whatever the reason, it is vain to attempt to persuade ourselves that we do not believe, as long as we do believe. And this will always be the situation concerning certain beliefs, if, as I hold, it is impossible for us not to have them because of our condition as deliberative beings.

A criticism often levelled at scientific descriptions and explanations of subjective phenomena is that of “reductionism”. I view this criticism as, in its substance, correct; not that we should refrain from describing these phenomena in scientific terms, nor that we should attempt to add, as is so often done, some holistic layer of “emergent phenomena” based on the questionable principle that the whole is more than the parts. Rather, I believe that these descriptions and explanations are themselves made in the terms of a physics that is incompatible with subjective phenomena, and that to accept them would be to accept that this outside point of view could abolish the inside one. But this abolition, as I have said, is not possible. A physics that has implications we cannot believe is itself a physics we cannot believe.

The reality of the truth-value of prescriptive assertions

Foremost among those things that we cannot nonbelieve is the existence of reasons for making decisions, that is, the existence of the right (correct) answer to the question “What to do?”. The answers (right or wrong) to this question are not descriptive assertions, in the classical sense, but instead prescriptive. They are of the form “Do this!”. They are not to be confused with simple predictions, such as “I will do this.”.

One may find this new category of assertions mysterious. What is their truth-value? In what sense can the proposition “Do this!” be true? First of all, such a proposition does have a negative: “Do not do this!”. Secondly, belief does not in itself constitute the truth of such propositions; we can be wrong. After having thought “Do this!”, we may change our mind: “No, instead, do this other thing!”. We may also reconsider afterwards: “I should not have done that.”. If belief in the assertion was its truth, we could not change our minds, that is, feel that we were wrong. The act of deliberation itself would be meaningless – any conclusion we reached would be right, by the mere fact that we reached it. It would be like looking in a meadow for the blade of grass that we will have found in it.

If the truth-value of prescriptive assertions is not defined by our belief in their truth, then it exists independently of this belief. To search for the right answer to “What to do?” necessarily assumes that a certain answer is the right one, whether we find it or not. It would make no sense to search for it if we did not believe this; but it is impossible for us not to search for it, and it is therefore impossible for us to nonbelieve that a certain answer is right, regardless of our perception of its being right. It is in this sense that we cannot nonbelieve in the reality of the truth-value of prescriptive assertions.

Ends and means

We should not view deliberation as a purely factual search, such as “Given that I have a certain end, what is the best way to achieve it?”. If this were the case, what I call a “prescriptive assertion” would be no more than a descriptive assertion, in the usual sense: “Given that I have a certain end, here is the best way to achieve it”. But we also choose our ends. Even a completely “selfish” person has chosen to consider only her interests, excluding those of others. This implies at least her belief in the factuality of the possible future satisfaction of her interests, that is, if she conceives her interests in terms of obtaining pleasure and avoiding suffering, that she believes in the reality of her future pleasure and suffering17. She cannot believe that things that do not exist in reality are an end for her. But she will also have to believe that this future pleasure and suffering can be the result of her actions; she will therefore have to believe in the existence of a physical world, at least in this minimal sense. Finally, the satisfaction of her own interests will represent in many cases not one, but several at least partially conflicting ends; she will have to choose between qualitatively different pleasures, between pleasures in the near future and others more remote, to decide whether a certain pleasure is worth the suffering needed to obtain it...

It is also possible to imagine that an individual may view his “interests” in terms other than pleasure and suffering. One example is the idea (based on a misinterpretation of Darwinism) that our “real” interests are the propagation of our genes. Another results from a certain romantic individualism, for which our interests consist in something like “self-realisation”18. If some people do take such ends seriously, this only confirms the plurality of our possible ends, and thus the fact that these, like our means, are the result of a choice.

I believe that in reality this distinction between the choice of ends and that of means is artificial. In our real deliberations, both are intertwined. No doubt the temptation to posit such a distinction and to seek to eliminate the choice of ends by taking them as constants stems from our difficulty in conceiving on what basis this choice could be made, if we view it as free. I will return to the problem of free will. For the moment, let us just remark that the choice of means, once the ends are determined, is not necessarily less problematic in its mechanism. The solutions that a sentient being finds to achieve a given end are often “innovative”, and the hypotheses put forward by Penrose suggest that our brains allow for modes of problem-solving that could not be simulated by an algorithm, and are therefore not deterministic in the sense of computable determinism.

A meaning “for me”?

We cannot refrain from deciding, and cannot decide without asking ourselves “What to do?”; and we can only ask this question, like any question, if we believe it has a meaning.

We cannot say, “Yes, I give this question a meaning, but that is because I cannot do otherwise; but I do not believe that it really has a meaning”. If we don't believe it really has a meaning, we don't believe it has a meaning at all.

Nor can we say, “Yes, it has a meaning, but only for me”. This process of relativisation is often used also concerning “descriptive” statements in the classical sense. I think it is worth examining what it asserts.

“For me” may mean “this is what I believe”; then “x has a meaning for me” signifies “I believe that x has a meaning (but others, perhaps, do not)”. The assertion that x has a meaning is then not itself relative, but instead absolute. I can say, “For me the earth is flat”; the flatness of the earth remains an absolute question because it is true or false that the Earth is flat, independently of me. To say that prescriptive assertions make sense to a certain individual is then to say that this individual believes that they make absolute sense. This then grants my point: we all believe that prescriptive assertions have a meaning.

In other cases, the expression “for me” denotes a different kind of relationship between the statement and an individual. An apple may taste sweet to Anne, and sour to Valerie; its “objective taste” does not exist. This does not mean, however, that the taste it has objectively for Anne does not exist, as does the taste it has for Valerie! In this case, we could say that the having-a-meaning of x is an objective truth, but in relation to me. This relation could be the simple fact that it is indeed I who believe that x has a meaning; we are then back to the first interpretation of “for me”. The relation could also be the fact that the prescriptive assertion x is itself related to the entity “me” (if we accept the existence of such a “personal identity”19): it prescribes what I should do. It is a truth about me, in that sense; but a truth I believe in, just as I believe (or not) in the flatness of the Earth.

It is remarkable that this relativisation – this “true for me” – works as if “me” were an entity somehow beyond the world, and could as such somehow bring the very truth in question with it into its retreat. Given that we are part of the world, our very view of the world is part of the world. If we believe that prescriptive assertions have a meaning “for us”, we believe that they have a meaning, period.

Ethics as a theory of the correct answer to the question “What to do?”

I have so far discussed prescriptive assertions; I think we can also call them ethical assertions. More precisely, I believe that a prescriptive assertion – the assertion “Do this!” – is true if what it commands us to do is what ethics commands us to do; and that therefore deliberation – the pondering of the question “What to do?” – is the search for the ethically right action.

I do not say this in a normative sense; that is, that all deliberation should be the search for the ethically right action. I am saying that in fact it is such. I propose to define ethics as the theory of the right (true, correct) answer to the question “What to do?”.

I will be told that I am free to define words as I wish, but that my “ethics” is not ethics in the ordinary sense of the word. I do not believe that this objection is justified. More specifically, I believe that my definition of ethics follows from the common usage of the term if only one ceases to make an arbitrary exception regarding decisions that concern only oneself, and accepts the absolute truth of prescriptive assertions.

Selfish and ethical behaviour are usually contrasted. The point of ethics, it is said, is to lead us to consider others and respect their rights and interests, instead of paying attention only to ourselves. Some ethical conceptions make this restriction explicit. Contract theories, for example, essentially require us to respect the terms of our “contract” with others, but concerning ourselves we are “free” to do “as we please”20. At least one ethical theory, however, governs in principle all our choices, placing on an equal footing those that concern ourselves and those that concern others: for hedonistic utilitarianism, we must act to maximise net happiness in the world; therefore, an act that increases our own happiness without affecting that of others is ethically obligatory, just as is an act that increases the happiness of others.

This fact is rarely perceived, perhaps simply because there is little need to order people to pursue their own happiness. Yet such a command is still ethical in nature, even though we usually abide by it without the aid of an elaborate ethical theory. The same is true of many propositions in physics; we do not need to study fluid mechanics before drinking a glass of water. Physics would nonetheless be artificially mutilated if we removed from its domain what happens when we drink a glass of water; just as it is an artificial mutilation of ethics to remove from its domain “trivial” prescriptions such as those commanding us to consider our own interests.

Among the commonly mentioned ethical theories, there is at least one other that gives us obligations in choices that concern only ourselves21. This is the so-called “egoistic ethic”, whose single command is: “Maximise your own happiness!”. The fact that it is frequently mentioned as an ethic, even only as a “textbook case”, shows that common use does not exclude, at least in principle, decisions that concern only ourselves from the scope of ethics. This egoistic ethic, like hedonistic utilitarianism, governs in principle all our choices.

However, the basic reason why I say that ethics should be defined as the general theory of the true answer to “What to do?” is that all deliberation is fundamentally altruistic. Even if I am thinking only of “myself”, I am necessarily thinking of a future “myself”. My actions cannot determine the pleasure or suffering I experience at the time I choose them; they will necessarily determine my future pleasure or suffering. We are used to taking for granted our concern for ourselves. The fundamental difficulty we have in justifying ethics is often expressed by the question “Why should I rationally care about others?”, and many feel there is no possible answer. Rarely do we ask ourselves “Why should I rationally care about the feelings I will experience in five minutes?” We can just as easily say that these future feelings are completely indifferent to us! We are rarely totally indifferent to how we will feel in five minutes, just as we are rarely completely indifferent to the fate of people close to us; on the other hand, we are often rather indifferent to how we will feel in thirty years. If this were not the case, tobacco sales would suffer greatly.

Therefore, the idea that there is a radical difference between a concern for one's own – necessarily future – interests and a concern for the interests of others appears as a dogmatic and artificial construct, with little justification in either theory or practice. It is in this sense that I believe that all deliberation is altruistic; the interests it takes into account are always those of an “other”, whether that other is another individual or our future self.

“I find this hard to believe”

There remains an objection to this conception of ethics: our decisions are not, in fact, always ethical, even by the ethical standard that we do recognise. It is perfectly possible to say “I see what I should do, but I cannot bring myself to do it”22.

I believe, however, that this objection can be answered if we regard prescriptive assertions as possessing a truth-value, whether or not we know this value. It is not our verbal assent to a prescription that makes it true; nor is it the fact that we believe we assent to it.

It may be useful to draw a parallel with assertions that are descriptive in the classical sense. When a would-be parachutist finds himself unable to jump from an aeroplane, is it not because he cannot entirely convince himself that doing so is safe? He may well insist that he knows it is safe, and rehash a hundred times the facts that prove it is safe. But somewhere inside him the belief remains that there is danger. It seems to me that this implies, at the very least, that we are not quite “individuals”, in the sense of being indivisible. Consciousness is not an illusion (in whose eyes would it be one?), but its unity may well be illusory, at least in part. Hence the fact that one part of our consciousness is convinced of a fact does not prevent other parts from believing the contrary.

We often know without knowing. “I can't believe it” is often said of the death of a loved one. We may act as if he were still here; we may set the table for him, “out of distraction” – or rather, because a part of us still does not believe in his death.

To return to prescriptive assertions: we may well know that what we are about to do is not what we should do; because, for example, it will cause others more suffering than it will bring us pleasure. But we know this without fully knowing it; just as we know, for example, that the pleasure of smoking a cigarette may cause us much suffering in thirty years while still finding it hard to believe. In this light, it is because part of us does not really believe what we think we believe that we act in contradiction with our stated beliefs; and this is true whether the issue is descriptive (in the classical sense) or prescriptive.

A few months ago I climbed to the top of one of the towers of the Basilica of Fourvière in Lyon. This tower, which is open to visitors, has been climbed by hundreds of people every day for ages; I knew that it was not going to collapse just because I put one foot wrong! Everything told me that I was safe. Yet I felt dizzy as I climbed the steps; I was filled with the dread that they would break under my weight. I climbed slowly and reached the top with clenched teeth. My fear was undoubtedly irrational, but it was nonetheless real; it reflected a real belief in me that I was in danger.

I see no difficulty in viewing the problem of our non-compliance to our own ethical beliefs in the same way. We simply believe them only in part.

Description and prescription

My thesis is that we believe in prescriptions as we believe in descriptions; we believe that their content is true (or false). I also speak of their “objective truth” and their “reality”. A famous assertion – the origin of which I cannot find, and which I quote from memory – was in substance that nowhere in the universe is there anything that would resemble a prescription; and that prescriptions, therefore, do not exist as such. Moral duties, right and wrong, would only reflect our personal, “subjective”, preferences, cultural or otherwise. There would be no such thing as real ethics.

I admit that neither can I clearly define in what sense ethical prescriptions are real objects. However, I believe that the generally accepted idea that “material” objects exist is equally problematic. The verb “to exist” seems transparent, but transparency is like opacity in that it shows no content. In fact, in modern, quantum physics, the issue of the very existence of an objective reality has become highly opaque; the “standard” (so-called “Copenhagen”) interpretation is that this issue is itself meaningless. Physics is a mere set of “recipes” for predicting future observations from past ones. Everything else is no more than “gratuitous speculation”23. Paradoxically, according to this interpretation, utility (for humans), that is, a subjective, indeed, prescriptive entity, is all that is left – physical reality has disappeared, bringing with it the reality of non-human animals.

Classical, pre-quantum mechanics, which I term “Laplacian”, would appear to impart a greater consistency to physical reality. This vision remains today, as noted above, a kind of ideal model of physics, including for many scientific minds who are eager to believe in a cold and hard reality. Therefore few perceive to what extent the very logic of Laplacian physics itself leads to a dissolution of the notion of reality. I will devote the next section to a brief description of this Laplacian worldview and will highlight some of its weaknesses.

In any case, I would like us to suspend somewhat our habitual certainties according to which, to be “real”, a “thing” must be made of matter and be located “somewhere in the universe”. We are not sure what it really means for a stone to be real. Nor are we sure in what sense mathematical truths exist. Nor can I say precisely in what sense prescriptive assertions exist. I only know that neither stones, mathematical truths, nor ethical truths can be entirely taken out of existence. I believe that these things exist in the world, and therefore exist there objectively, are real. I will not make sharp distinctions between these notions, because I do not believe in those that are commonly made.

In particular, I think that if a prescriptive assertion, of the form “Do this!”, is true, then it describes a part of reality. The descriptive and the prescriptive are classically opposed; it is better to view instead every assertion as descriptive. This is why I also speak of descriptive assertions “in the classical sense” for those that are usually considered as such (the mass of a stone, for example).

Animals as moral agents

Anti-speciesist moral theories commonly distinguish between the twin notions of a moral agent and a moral patient. Humans are typically both moral agents, which means that they can (and should) act ethically, and moral patients, meaning that they should be taken into consideration when ethical decisions that concern them are made (their interests should count, and/or their rights or dignity should be respected...). Non-human animals, on the other hand, are generally only viewed as moral patients: we are to care about them, equally as for humans, but they have no duties, because they are incapable of ethical reasoning, just as are young human children, for example.

If instead, one accepts, as I propose, that all deliberation is by definition an ethical activity, and that there is no difference in nature between the deliberating individual's consideration for his own (future) interests and for the interests of other beings, then it appears that every animal who deliberates is a moral agent, in the same sense as the term can be applied to a human.

This does not mean that there are no distinctions to be made concerning the level of complexity and abstraction that an individual can reach in her ethical reasoning. The same applies to ethics as to physics. Deliberating animals are also necessarily physicists; they foresee consequences of their actions. Only a few among them, namely some humans, can build complex and abstract physical and/or ethical theories; much more often, the ethical and physical horizon is more limited; it comprises what is perceived, the near future, proximate interests and the interests of one's family or group. This limited ethics and physics is nonetheless an ethics and physics.

When we scream in fear and pain, we are saying: “This is bad!”. The scream of a pig being slaughtered says the same thing: that what is happening is bad. The anti-speciesist says the same thing: that the slaughtering of the pig is bad and says it for the same reason for which the pig says it. This same assertion, from whomever it comes, has the same meaning and the same nature: it is an ethical assertion.

If we are to believe the words that the vegetarian writer J.M. Coetzee puts into the mouth of one of his characters24, it was in part the ethics of a hen that led to the abolition of the death penalty in France:

As for animals being too dumb and stupid to speak for themselves, consider the following sequence of events. When Albert Camus was a young boy in Algeria, his grandmother told him to bring her one of the hens from the cage in their backyard. He obeyed, then watched her cut off its head with a kitchen knife, catching its blood in a bowl so that the floor would not be dirtied.

The death-cry of that hen imprinted itself on the boy’s memory so hauntingly that in 1958 he wrote an impassioned attack on the guillotine. As a result, in part, of that polemic, capital punishment was abolished in France. Who is to say, then, that the hen did not speak?

5. The Laplacian model of reality

What I call the classical, or Laplacian, model of reality emerged in the 17th century with Galileo and Newton, replacing Aristotle's physics which was dominated by finalist, animistic ideas about the nature and desires of bodies. The Laplacian model formed the basis of scientific rationalism and dominated the scientific worldview until the early 20th century. Einstein's theory of relativity (1905, 1915) still fits into this framework, which was only subverted in the 1920s when quantum mechanics made it untenable, without however providing any alternative view of physical reality.

I hope it will be clear from the short analysis I will propose of the Laplacian model that it is the paradigm that we “spontaneously” tend to view as the model of scientific description. When we insist, for example, on rejecting the notion of free will because our choices must be determined by something, this requirement is evident neither in the Aristotelian framework nor in that of quantum mechanics, which implies that certain events do indeed occur without reason. I do not believe however that the model, or rather non-model, that quantum mechanics proposes gives us a satisfactory account of free will; my purpose here is to shake some of our certainties concerning the validity of the Laplacian model. I will also show that this model does not itself live up to its own requirement that everything should happen for a reason.

I name this model “Laplacian” in reference to the striking formulation that the physicist Pierre Simon de Laplace (1749-1827) gave of the notion of determinism25:

An intelligence which, for a given moment, would know all the forces with which nature is animated and the respective situations of the beings that compose it, if moreover it were vast enough to submit these data to analysis, would embrace in the same formula the movements of the largest bodies in the universe and those of the lightest atom: nothing would be uncertain for it, and the future, like the past, would be present to its eyes.

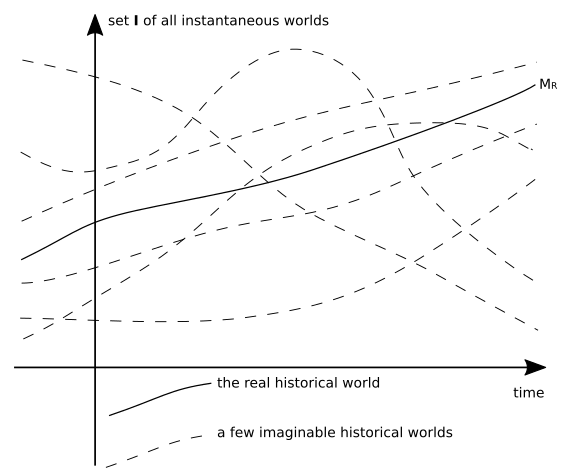

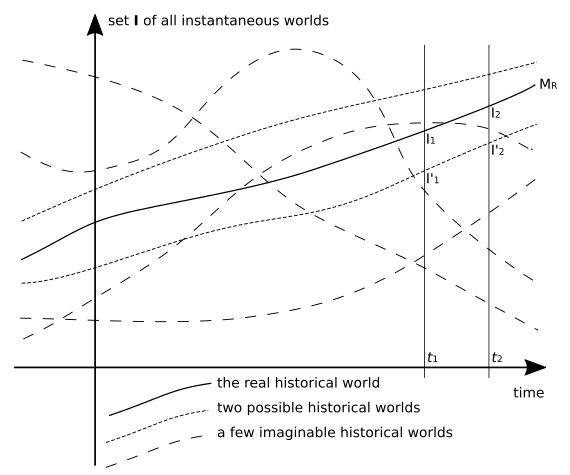

In this view, reality – all that exists – consists of a finite or infinite collection of objects – the “beings” mentioned above by Laplace – each of which can be characterised by a number of properties that may vary over time; knowledge at a given moment of the list of these objects and their properties constitutes a complete description of reality at that moment.

A simplified view that I will often use is that of billiard balls. In an ideal billiard game, the balls move at all times according to a well-defined and computable law. As long as they do not meet a wall or another ball, they move in a straight line at a constant speed; when they collide, they bounce back elastically, following a simple law that brings into play their intrinsic characteristics (mass, radius), their motions and positions. The evolution of the whole can be complex if a large number of balls are involved, but always remains entirely predictable, at least in theory, by an “intelligence”, as Laplace calls it, informed of the laws of motion as well as of the mass and the situation (position, speed) of each ball. The “billiard ball” image of the world assumes that the whole world is a vast collection of such balls moving in three-dimensional space.

Of course, classical physics has never seriously proposed such a simplistic model of reality. The “billiard balls” picture remains relevant, however, because it captures the basic logic of classical physics, with a few subtleties. In classical physics, in the place of balls, we have “material points” – dimensionless “atoms” or “particles” that possess, for example, mass and charge – and attractive and repulsive forces of a more complex form than the simple contact repulsion that makes balls bounce. To these material points were later added fields, such as the electric field, that are distributed throughout space, mediating the forces between particles but also evolving according to their own laws. It followed that the complete knowledge of which Laplace spoke also includes that of the fields, and therefore an infinity of variables, since it is necessary to know the intensity of the fields at each point of space26. Despite this, the “billiard ball” model has all the features that I will discuss of the Laplacian model. If subjectivity cannot find its place in a “billiard ball” model, it cannot find its place in Laplacian physics27. I will often speak as if Laplacian physics were only about billiard balls because this is a simple image that allows us to highlight its workings and limitations.

It should be noted that classical physics never really succeeded in proposing a consistent and plausible theory of reality; there were always details that could not be ironed out28. The Laplacian image nevertheless remains as a paradigm for any physics that claims to be objective and allows for an observer-independent reality, because quantum mechanics proves incapable of providing such a model.

The completeness of the Laplacian model

Completeness means that all that can be said about the world is deemed to be contained in the “respective situations of the beings that compose it”; that is, to use our billiard balls image, in the position and speed of each ball.

In particular, the movements of our hands, our thoughts, our feelings, all of this would be the “mechanical” colliding of these balls according to the laws of motion that govern them. To say that I perceive the world is only to say that some of these balls, those of the world outside my body, collide in a certain way with the balls of my body, creating movements that will, in passing from one set of balls to another, end up provoking certain movements and dispositions of balls in my brain or elsewhere, movements and dispositions which will of necessity, in some way or another, constitute my perception. My feelings and emotions will in the same way be dispositions and movements of balls somewhere in me. When I act on my perceptions and feelings, for instance when I write down my thoughts on a sheet of paper, it will be because these dispositions and movements will have in turn, still following the same “mechanical” laws of motion, provoked certain movements in yet other sets of balls, which I call my hands, which will produce the writing on the paper.

Because of this completeness, the balls themselves have no “interiority”. The expression “billiard balls” is misleading in this respect. The physics of real billiard balls moving on a table describes some of their characteristics, such as their position and speed, but these parameters are relative to objects that exist independently of them and have many other characteristics that give them existence: colour, roughness, chemical composition, solidity... On the other hand, in the Laplacian “billiard ball” model, the balls have no colour or roughness; they are not made of “something”. All that can be said about them is a small collection of numbers, namely their mass, radius, position and speed. The “radius” itself is not the boundary between a full interior and an empty exterior, but a simple parameter determining if and when a “collision” with another ball will occur. This “collision” will be a change in the movement of the “centre”; but what is this centre the centre of? The answer can only be: of nothing. It is but a moving point in space. Its only existence is through its determining “collisions”, that is, events affecting other “balls”, which are themselves no more than points of the same kind. Yet all of space is points; what is special about these particular ones? There can be nothing, outside of the fact that their positions are those described by this particular collection of numbers...

If there were ever anything else to be said of this reality, if the “balls” possessed a reality beyond these few numbers, this additional reality would be unknowable to us; for our knowing it would be the same thing as particular positions and movements of certain balls in our brains, and, under the deterministic laws of movement, these positions and movements are entirely determined by those of all the other balls, and therefore cannot depend in any way on this additional reality.

As previously mentioned, the real picture proposed by Laplacian physics, based on particles and fields, is much more complex than the “billiard ball” model. The absence of interiority remains, however; the world has no “substance” and remains entirely describable by a collection of numbers, which appear to describe no more than themselves. It is therefore difficult to see how the world could actually be anything other than a collection of numbers. It is paradoxical that the Laplacian paradigm, often perceived as the epitome of “materialism”, actually dissolves the world into a substanceless abstraction.

A reversible determinism

The Laplacian model is deterministic, in a sense defined by the above quotation: the world is governed by a set of laws such that if I know its state at a given moment (the set of numbers that describes it), I can in principle deduce (calculate, compute) its state at any future moment. The word “determinism”, however, refers to something more, that includes the notion of a cause-and-effect relationship: that the state of the future world is entirely caused by its present state. This common interpretation is suggested by the origin of the word: the future is determined, that is caused, by the present, since a given present state can produce only one possible future state. It thus seems natural to equate physical, Laplacian determinism with a principle of total causality (“everything that happens is determined by what previously happened”); but paradoxically, as I shall show, the very notion of causality is an empty word in Laplacian determinism.

Significantly, Laplace's quotation gives the same role to the past and the future: “and the future, like the past, would be present to its eyes”. Indeed, all classical models of physics are reversible concerning time. This means, in graphic terms, that if I film any event, and then play the sequence backwards, the reversed sequence I see still satisfies the same laws of evolution. This property is verified in the “billiard ball” model: both the uniform rectilinear motion and the changes in motion during collisions are reversible.

This is a property shared by all current physical theories, including, with some qualifications, by quantum theories29.

Laplacian determinism implies that if I know the state of the world now, only one single state can follow at a given future time; but because of its symmetry between the past and the future, it also implies that the present state can stem from only one single possible state at a given past time. Does this mean that the present causes the past? The present “determines” the past as much as it does the future if by determination we mean that for a given present, there can be only one past, just as there can be only one future. And Laplacian determinism says no more than this. The notion of causality, which is always dissymmetrical – the past causes the future, but not the reverse – cannot, therefore, be founded on this basis alone.

This paradox illustrates the contrast between Laplacian reversibility and common sense: we do not feel that the past and the future are symmetrical at all. We view time as having a well-defined “arrow”, as being able to “move” only in one direction; and causes as being all on one side – which we call past – and effects on the other – which we call future. But it seems impossible to derive such an arrow from completely symmetrical evolutionary equations; the problem of the “arrow of time” has been one of the major difficulties of physics since the 19th century.

I will later return to the notion of causality because it is linked to that of laws – itself problematic in the Laplacian framework – and to that of free will, which I view as an unavoidable ingredient of the subjective.

The epiphenomenalist hypothesis

Epiphenomenalism is the idea that sentience (subjectivity, consciousness) is only an epiphenomenon of the physical world; that, in short, consciousness may “look but not touch”. This is less a thesis that anyone actually defends than the unpleasant conclusion to which many attempts to account for sentience within a Laplacian framework seem to lead.

I said above that because of the completeness of the Laplacian paradigm, our sensations, feelings and emotions are necessarily identical to certain “dispositions and movements of balls”, or, in the terms of a more realistic model, to the dispositions and movements of particles and the states of the fields inside our brains.

Intuitively, many people, including myself, find it difficult to believe that sentience can be “just” that. At the very least, it is not clear how particle movements and other “mechanical” processes can be a sensation; subjective sensations and phenomena seem to involve something more. I will return to more reasoned justifications for this feeling. Here I only want to note that if we try to make sentience into “something more” while remaining within the framework of the Laplacian model, we necessarily end up with an epiphenomenalist position.